CIO Viewpoint: The Four Asian Tigers - How are they doing now?

Returning to normalcy is now the key focus among governments, corporates, and individuals. The Economist has issued a "normalcy index" to track how social activities (sports attendance, time at home, traffic congestion, retail footfall, office occupancy, flights, film box office, and public transport) have changed and recovered from the pandemic.

Slightly different from our intuition, mainland China is not at the top of the list. However, Hong Kong, which has implemented effective measures and suffered relatively few deaths, is currently ranked at the top, suggesting that it is the closest economy to resume pre-pandemic life.

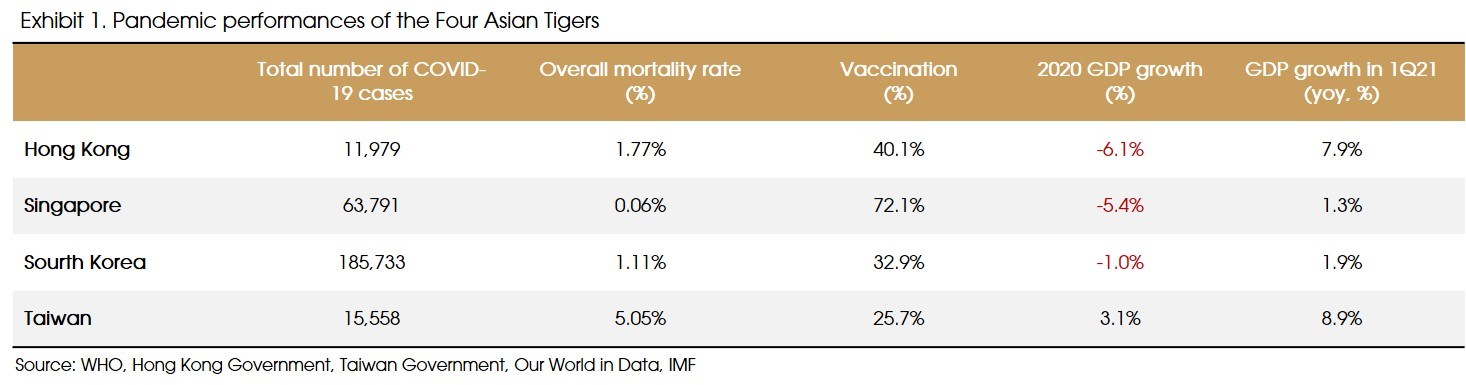

Other comparable economies show lower and diverging normalcy levels. Both Singapore and South Korea are having rising daily new cases due to the Delta variant, and Singapore had to postpone its travel bubble with Hong Kong a second time. Meanwhile, among the four economies, Taiwan has the highest overall mortality rate at 5%, the lowest vaccination rate (below world average), and the lowest normalcy level, according to The Economist (ranked 47).

However, relatively good handling of the pandemic does not mean a milder downturn in the economy. Hong Kong's economy took the hardest hit by the pandemic compared to the other three due to its heavy reliance on the service sector. However, good control of the pandemic is expected to enable Hong Kong to have a quick rebound this year (Exhibit 1).

For those who are not too young (e.g., born before 2000), the "Four Asian Tigers" may still ring a bell. The four economies (South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong) were once referred to as the "Four Asian Tigers", due to their rapid industrialization and growth between 1960s and 1990s.

Such success in growth lifted these economies from middle-income to high-income economies and served as role models for many developing countries, but none has managed to follow a similar path so far. A report by World Bank (in 1993) addressed the four economies as "The East Asian Miracle".

Let's leave the analyses of how the Four Tigers achieved such success and whether it is replicable by other countries to the academia. We will just take a look at their development trajectory, their respective strengths, and some investment implications.

What's behind the "Asian Miracle"?

From 1960 to 1990, Asia has become wealthier faster than other regions in the world. However, this growth has not occurred at the same pace all over the continent. The western part of Asia grew at the same pace as the rest of the world, but countries in the eastern half turned in a superior performance of achieving 3-5% annual growth. However, such impressive achievement is still modest compared with the phenomenal growth of Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, which experienced powerful and intimidating economic performance during this period.

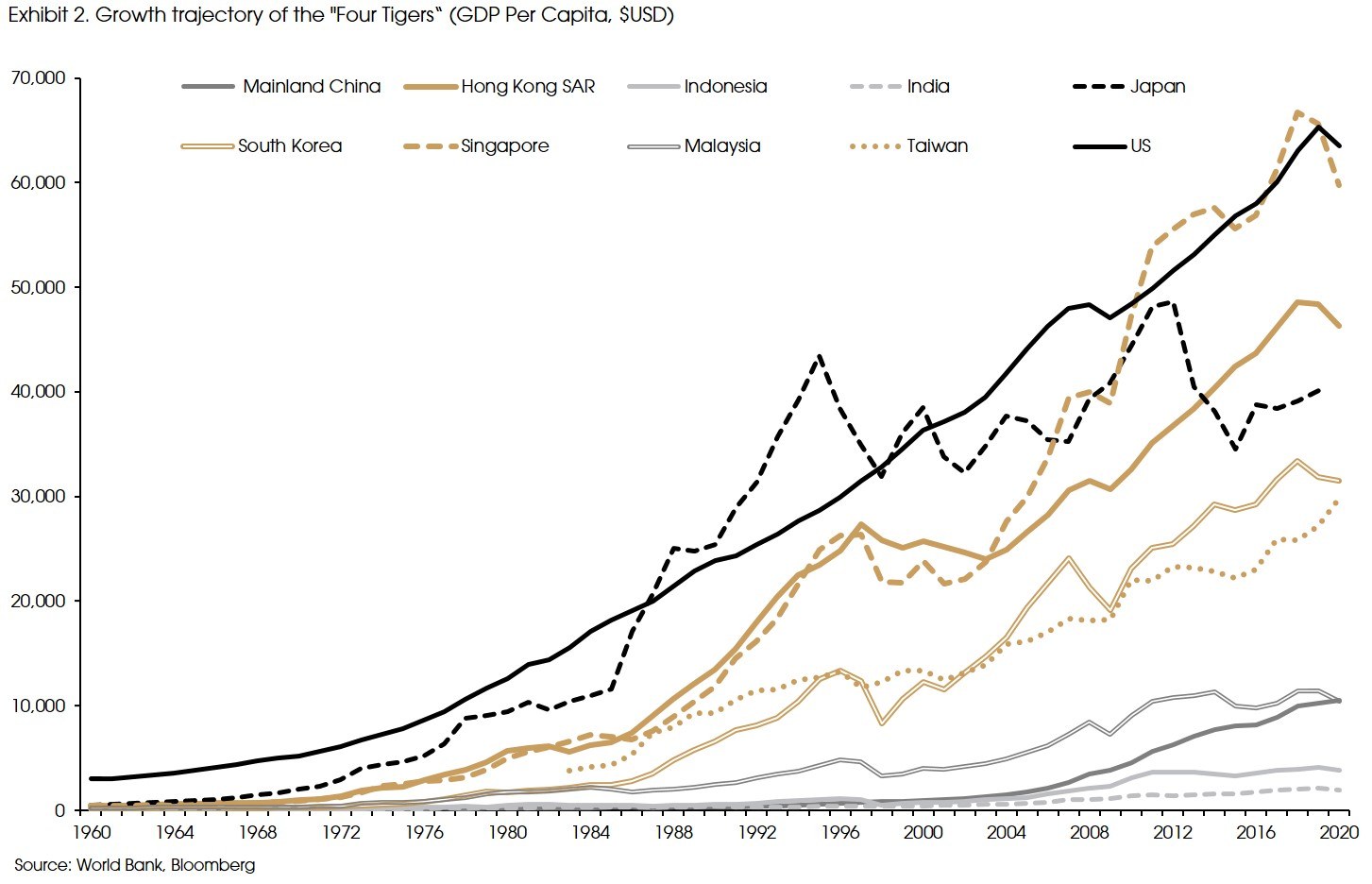

The four Asian economies maintained exceptionally high growth rates of more than 7% a year throughout three decades, and successfully leaped forward from low-income regions to high-income economies. GDP per capita (usually seen as an indicator for economic development) of the Four Tigers increased from USD 300-400 in 1960 to around or above USD 30,000 today, challenging that of the US and Japan (Singapore and Hong Kong have already exceeded Japan). Other Asian countries did not follow the same path (Exhibit 2).

Although no single theory can fully explain the success of the Four Tigers, few will disagree that they all benefited enormously from the broader context of globalization, which helped them to accumulate capital and technology.

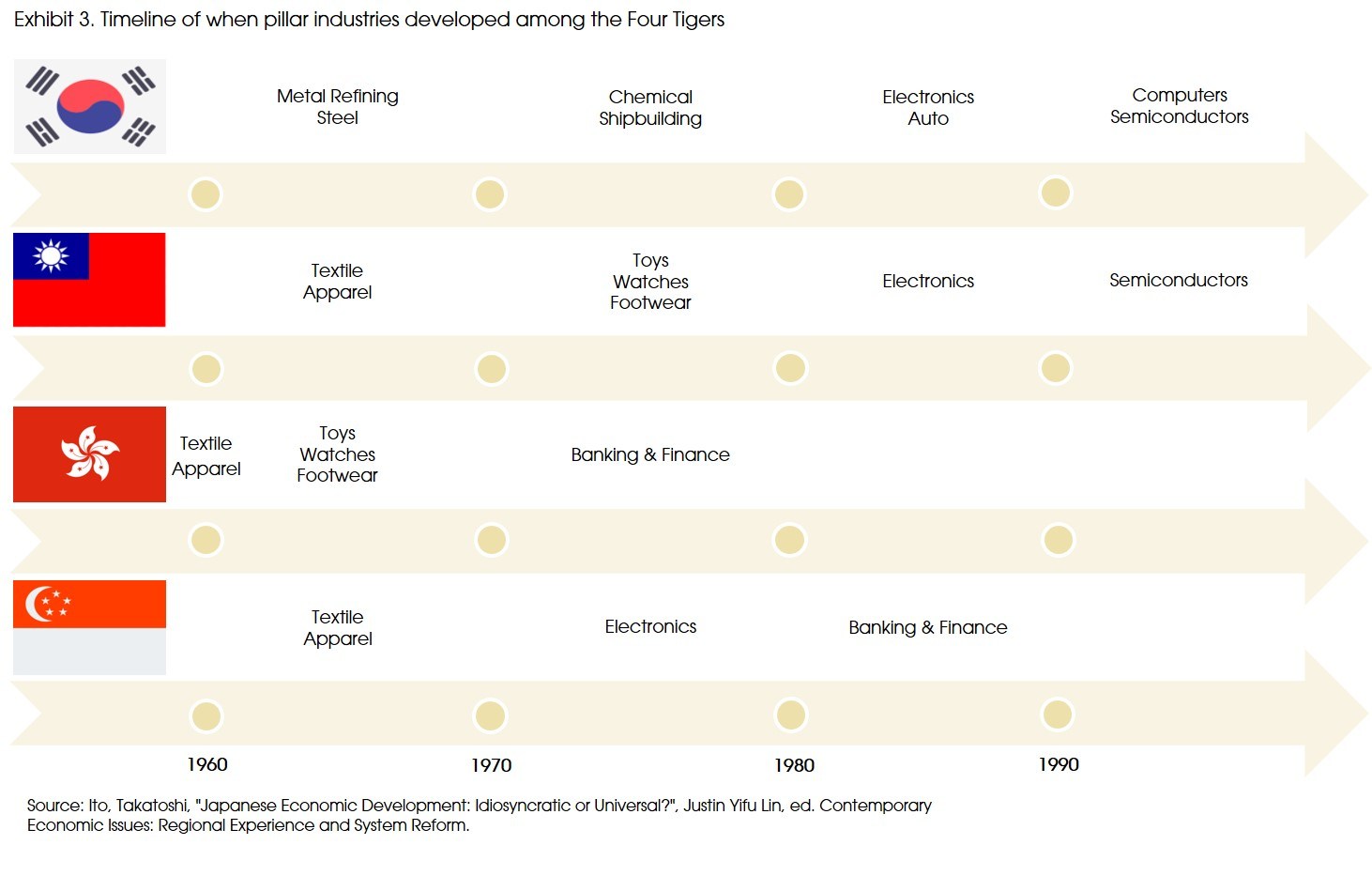

Moreover, at different stages of their development, these economies developed different key/pillar industries, almost solely based on their comparative advantages determined by factor endowments. With economic development and capital accumulation, factor endowment structures improved and led to the shifts in key/pillar industries gradually from labor-intensive (e.g., metal refining and textile) to capital-intensive (e.g., auto, chemical, electronics) and eventually technology/information-intensive (semiconductor, finance) (Exhibit 3).

Such a development path sounds natural and simple, but few other Asian countries managed to follow. In many economies, government intervention led to distorted market prices, with labor and capital being allocated to industries with little comparative advantage (e.g., government supports industries that are not profitable for non-economic purposes), and resulted in low efficiency in the economy. All of these impede growth.

On the other hand, governments in the Four Tiger economies intentionally made policies to facilitate the industries with comparative advantage. Such measures include the maintenance of export-oriented policies, low taxes, and minimal welfare states.

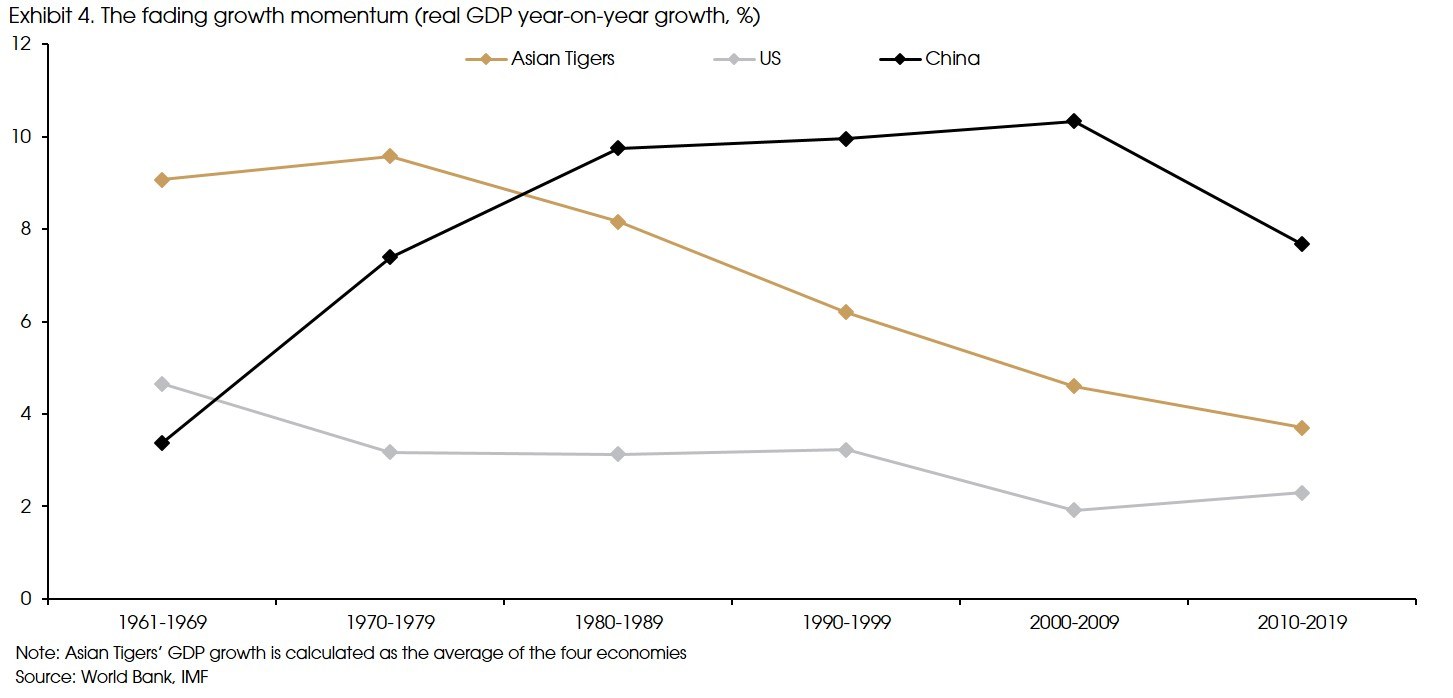

However, after the fast development, growth in these Four Asian Tigers slowed down since the 2000s. The aging population, increasing input costs, relatively small sizes of these economies, the recent anti-globalization headwind, and the increasingly complicated relation between the US and China all contributed to the declining growth. Moreover, as China further opened up and joined WTO in 2002, supply chains have been gradually transferred to China (and recently to other developing Asian countries) from the Tiger economies since then.

As a result, average GDP growth of the Four Tigers decreased from more than 6% in 1990s to 3.7% in 2010s, and even below that of the US in several years during the recent decade.

Current status: still have plenty of strengths despite the moderated growth

Even with lower growth, the Four Tigers still have plenty of strengths and play important roles in the global economy and financial market.

South Korea has a highly developed manufacturing sector, from shipbuilding, auto, to chemical, electronics and semiconductor, and has built up strong global brands from smartphones to K-pop idols. Taiwan has made itself an essential player in global middle-to-high-end manufacturing supply chain, especially in electronics and semiconductor sectors.

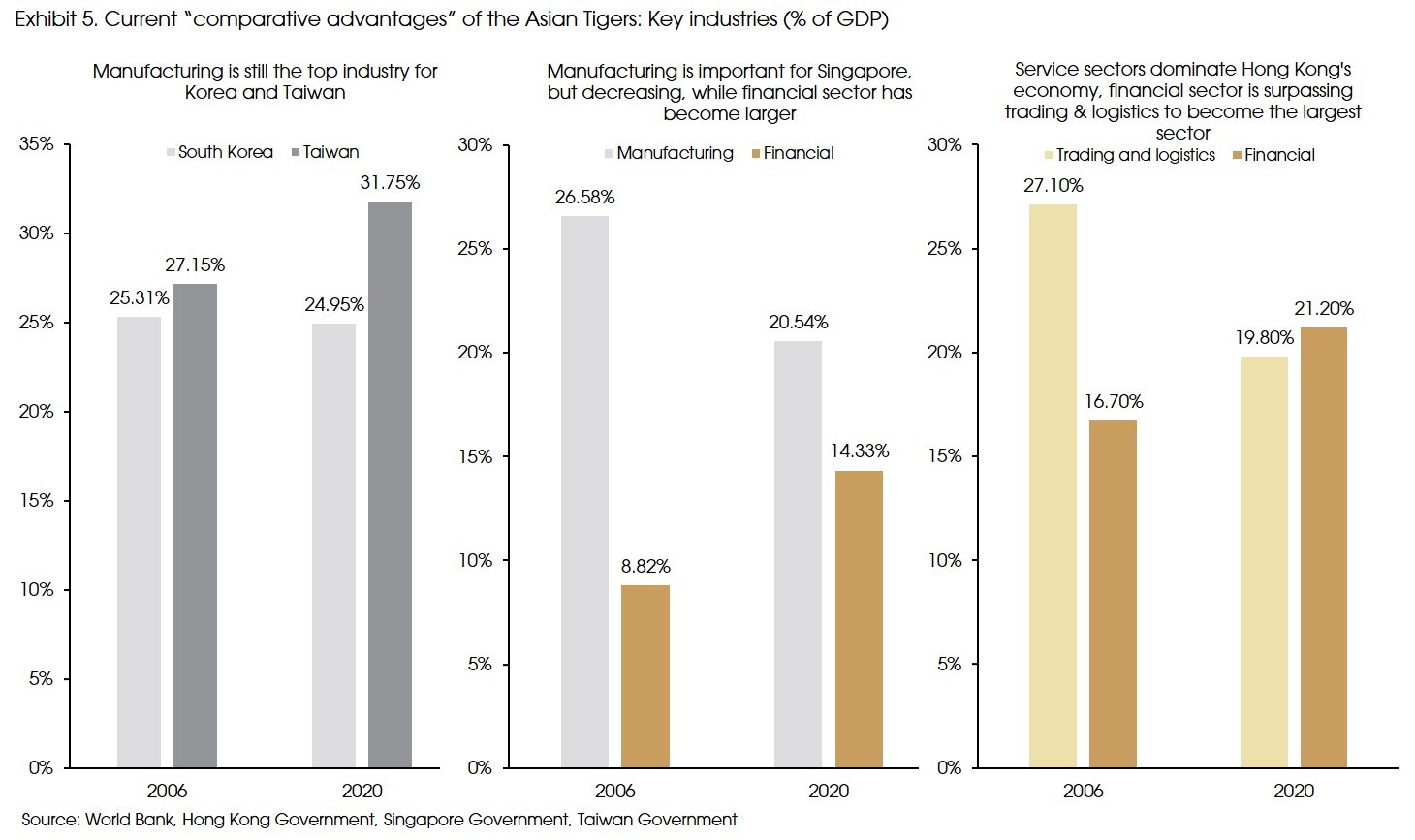

(Exhibit 5, left panel) Manufacturing sector continues to play a key role and accounts for a higher share of GDP in both South Korea and Taiwan, compared with other high-income economies.

Meanwhile, Singapore has a more balanced share between manufacturing and financial sectors. However, in recent years, financial sector has played an increasingly significant role in Singapore’s economy, at the cost of the decreasing manufacturing share (Exhibit 5, middle panel).

Hong Kong has a dominating service sector, with manufacturing sector only accounting for 1% of GDP. There are four “pillar industries” in Hong Kong: trade and logistics, professional/business services, tourism, and financial.

As a result of the social unrest in 2019 and the pandemic in 2020, Hong Kong’s economy fell into recession for two years. However, different from the previous recessions, the 2019-2020 recession mainly affected tourism sectors (which is the smallest among the four, only accounting for 5% of GDP). Other sectors were little affected, and the financial sector even overtook trade and logistics to become the largest sector in Hong Kong (Exhibit 5, right panel).

Looking forward, we think that the “comparative advantage” development strategy may continue to play in the four Asian economies, and the key sectors of these economies (i.e., manufacturing sectors in South Korea and Taiwan, and financial sectors in Singapore and Hong Kong) should remain competitive in the global market.

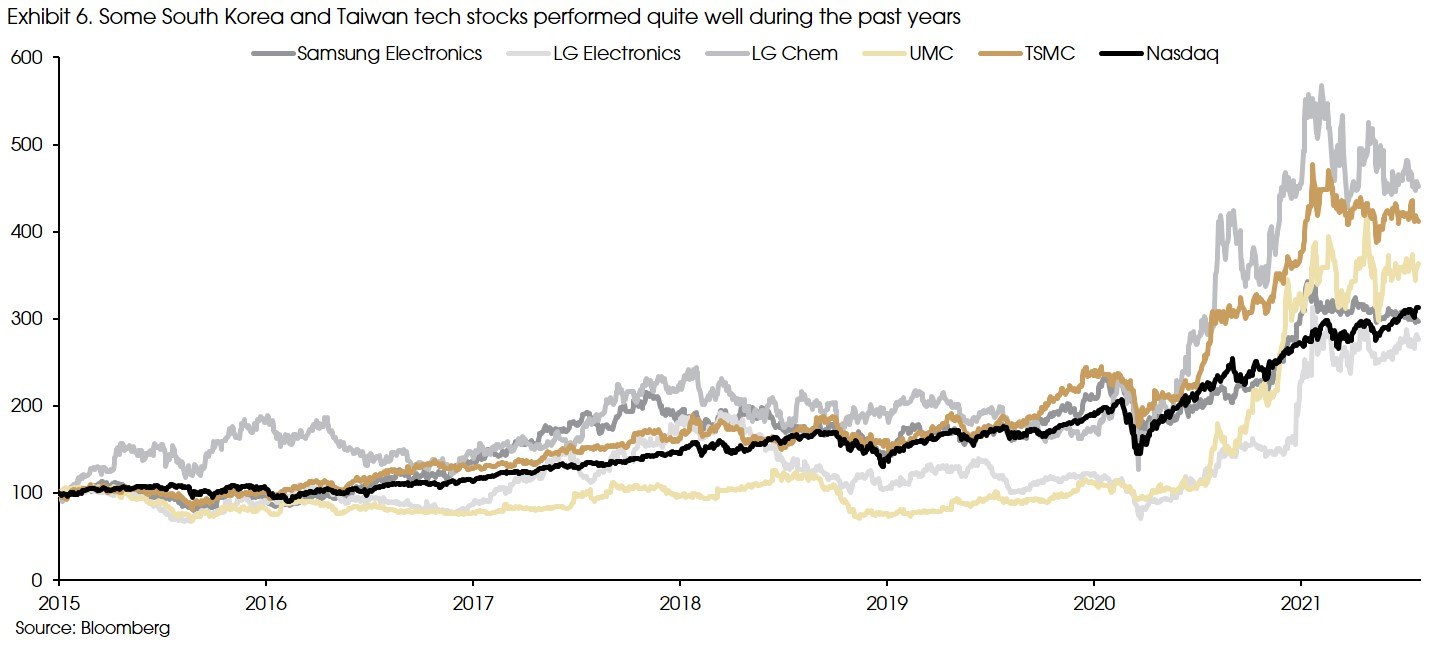

Taiwan and South Korea had a much milder economic downturn last year, thanks to their heavy reliance in manufacturing sectors, especially electronics and semiconductor. Large electronics and semiconductor companies in South Korea and Taiwan have been performing well in recent years, comparable or better than the NASDAQ index (Exhibit 7). The ongoing trend of digitalization and these companies’ current edges in the industry versus global competitors should continue to benefit themselves and the related sectors in South Korea and Taiwan.

Recently, an interesting discussion in the market has been on the comparison between Hong Kong and Singapore, or more specifically, whether Singapore will replace Hong Kong to become the global financial center in Asia.

For financial centers, first of all, a sizable, liquid, and deep capital market is needed. Hong Kong’s stock market is much ahead of Singapore. The stock market capitalization in Hong Kong is around USD 6.7 trillion, almost 10 times of Singapore (USD 690 billion).

Moreover, although Hong Kong’s stock market is already referred to as “less actively traded”, Singapore market is even worse. Its daily trading value is only around USD 360-400 million, compared with USD 15-25 billion in Hong Kong, and its daily turnover ratio is around 0.1%, while Hong Kong is arund 2%.

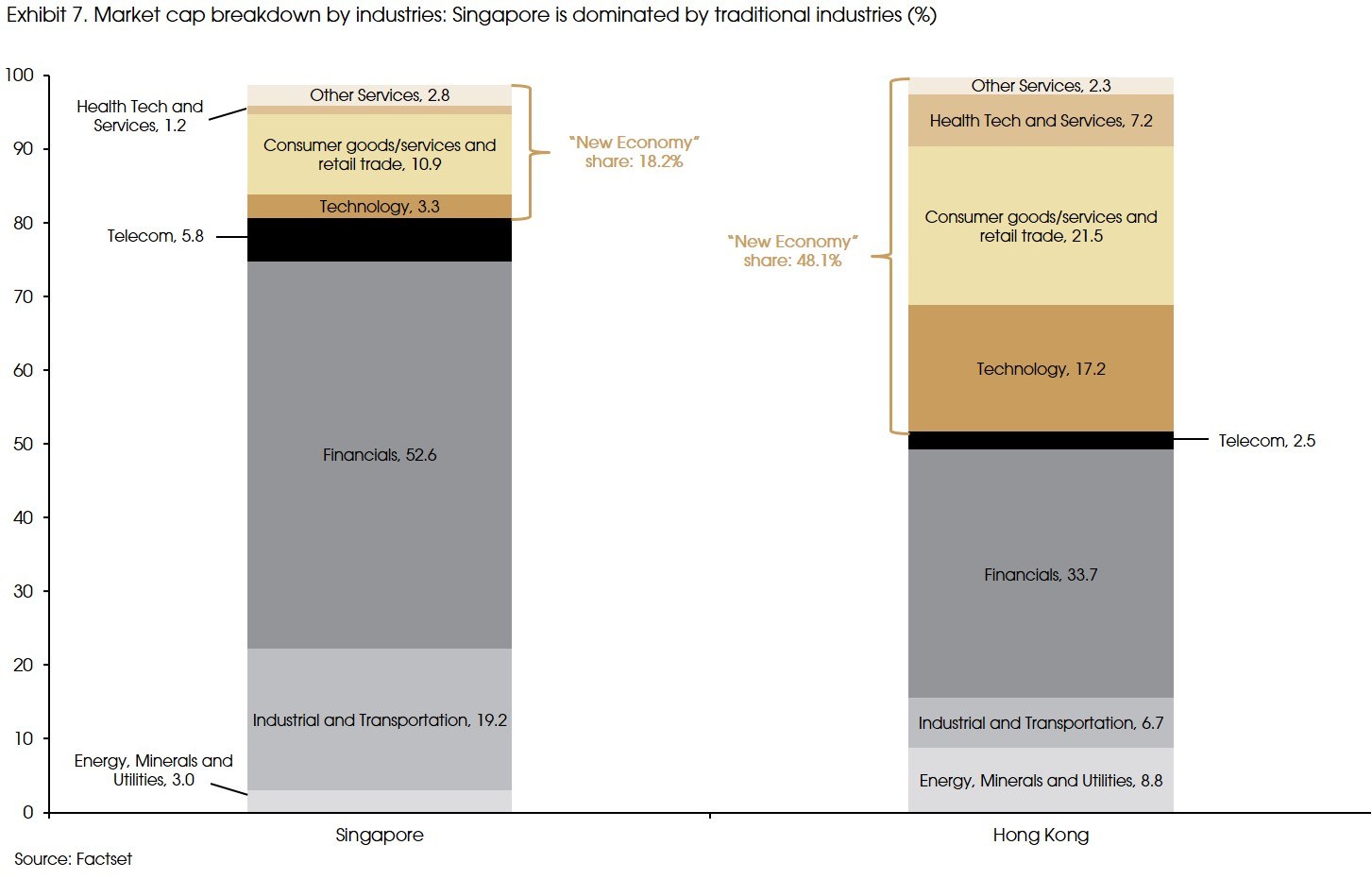

The low trading activity in Singapore is partially related to the sector distribution of its listed companies. Singapore stock market is dominated by traditional sectors (financials, industrials, and energy etc., accounting for more than 80% of total market capitalization, Exhibit 6). Hong Kong stock market had the same problem in the previous years. However, as more new economy companies from mainland China got listed in Hong Kong, traditional sectors’ market share decreased to around 50%.

Moreover, Hong Kong has been ranked at the top of the IPO fund raising league table for 7 years since 2009, and has never fallen out of the top 5. Meanwhile, Singapore seldom shows on the top 10 table, and even lost to Vietnam in IPO fund raising in 2018. New economy companies in Singapore, e.g., Sea, Grab, and Razor, usually choose to get listed in the US or Hong Kong market.

That said, Singapore does have a more developed bond market than Hong Kong. However, currently, the sizes of the two bond markets are similar, both at around USD 430 billion. The difference is that, as a sovereign country, Singapore’s government bond market is far more developed than Hong Kong. A developed government bond market is the key to derive a full range of benchmark yield curve, which is the anchor for bond pricing.

In that sense, the Singapore government started to issue bonds to facilitate the market in 1997, and Singapore’s government bond market was included into major bond indexes since 2005. The government bond market accounts for 40% of total bonds outstanding.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong is not a sovereign country and has only started its meaningful issuance of government bonds since 2009. Thus, government bonds only account for 5% of the total bond market.

However, Hong Kong has a large corporate bond market, mostly denominated in the US dollar. The prospective southbound trading of the Bond Connect could attract more investors and issuers in the Hong Kong market. Moreover, the government’s recent efforts in promoting its government bond and green bond programs may provide further support to the market.

We are aware of the concerns that the implementation of the National Security Law and the persistent geopolitical tension between China and the US might damage Hong Kong’s reputation as a global financial centre. However, we do not think that Beijing will take aggressive actions to intervene Hong Kong’s judicial system (see our previous newsletter).

On the other hand, the recent policy dynamic suggests that Hong Kong might become the only international market that Beijing trusts. The potential exemption from the cybersecurity check for Hong Kong IPOs could make Hong Kong the only destination for Chinese companies seeking overseas listings, which would further enhance Hong Kong’s unique status as a gateway for international investors to track China’s fastest growing sectors.

Moreover, the recently launched mutual recognition of funds (MRF) between Hong Kong and mainland China may lead to more fund inflows into Hong Kong. According to Boston Consulting Group, while Singapore may remain as a third largest wealth management booking center in 2023, Hong Kong may become the largest.

In sum, we think that Singapore will remain to be a leading bond market and wealth management center. However, to become a global financial center, sizable and deep capital markets are important. In that sense, Singapore may not be able to challenge Hong Kong in the foreseeable future.

Who might be the next Asian tigers?

The final question that we need to address is a “who next” question, i.e., who may become the next economy to enjoy fast growth for a sustained period.

A number of studies pointed out Vietnam, given its similarity to China, especially since it has begun to serve as the outsourcing destination for manufacturing firms moving out of not only from developed economies (e.g., Korea, Japan and Taiwan), but also from developing economies such as China and Malaysia.

In addition, the large population and consumer market, and the fast development in technology sectors in India and Indonesia may also suggest high growth potentials going forward (see our previous focus).

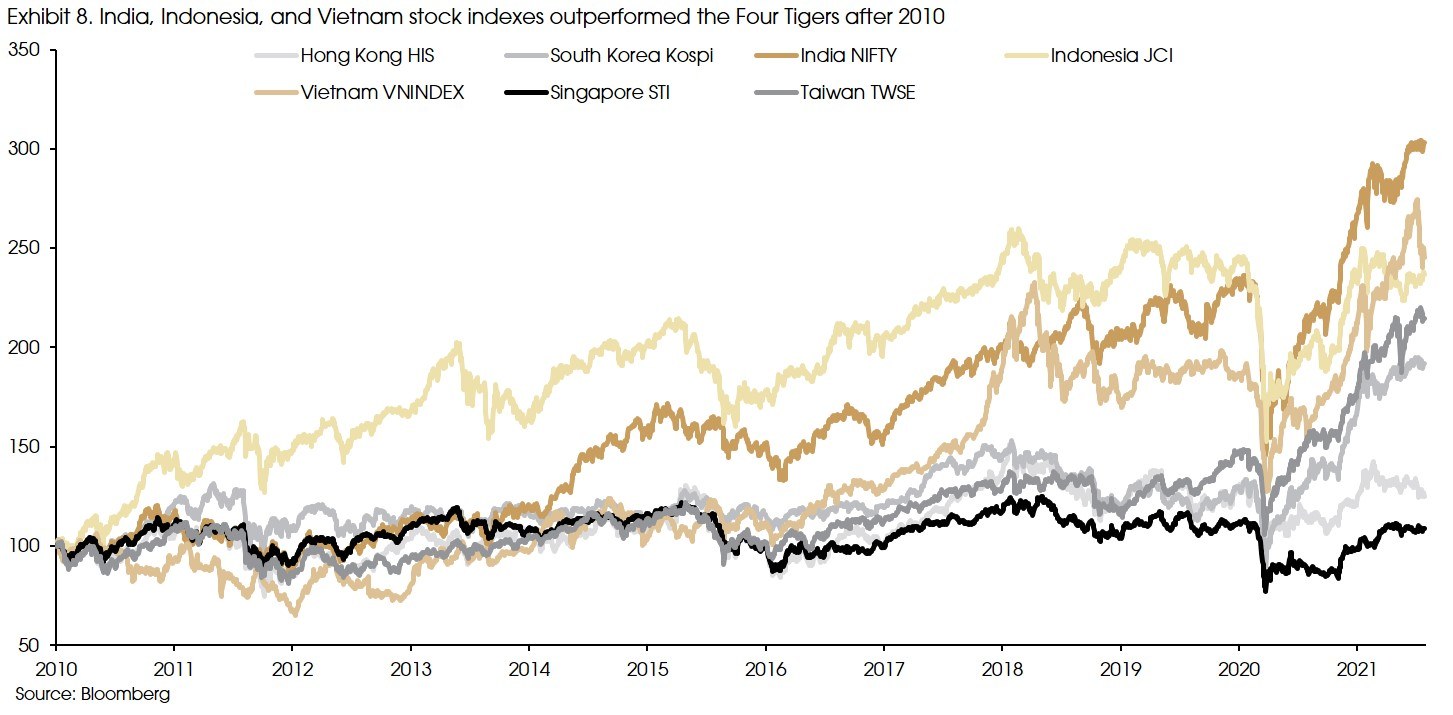

All three economies showed higher GDP growth compared with the overall East Asia before the pandemic, and the higher growth is expected to continue going forward, according to the IMF. Moreover, higher economic growth has led to better stock market performances in the three countries, compared with the Four Asian Tigers since 2010 (Exhibit 8).

The potential growth opportunities in these possible “next Asian tigers” may attract more interests from investors. However, foreign exchange risks and the lack of quality data or adequate research coverage on these markets suggest that the difficulty of stock-picking in these markets should not be underestimated.

Sources: World Bank, IMF, The Economist, Reuters, South China Morning Post, Goldman Sachs, Boston Consulting Group, GoVHK, HKEX, SGX, Contemporary Economic Issues: Regional Experience and System Reform, and CIGP Estimates.