CIO Viewpoint: Hong Kong - A Rising Financial Hub for China's New-Economy Companies

The world in 2020 is going through significant changes. The sudden outbreak of the COVID-19 has caught most countries unprepared and dragged the global economy into the deepest recession seen in decades. As a result, the breakdown of global supply chains has further accelerated deglobalization and led to rising friction between superpowers.

Against such a backdrop, companies' nationalities and the relations between their home countries' governments will matter even more than before regarding which markets to prioritize, which supply bases to cultivate, and the decisions of where to raise capital.

Tensions between the US and China have notably increased on various issues, including trade, national security, and Hong Kong's autonomy, and the pandemic just added new layers of complexity.

The Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act, passed by the US Congress in May, would require Chinese companies to provide access to their audit working papers to keep listing in the US. Any companies that fail to comply with the Act could be forced to delist from the US exchanges by January 2022.

The US-China trade war, more strict listing rules, and the bans on Chinese companies' access to the US market are all threatening the future of the Chinese firms listed in the US. Such contentions and fragilities of the US-China relation have urged more companies to consider secondary listings in safer harbors closer to home. Hong Kong is a popular destination of focus.

A Potential “Coming Back Wave”: More New-Economy Firms on HK Market

In 2015, there was a "coming back wave" among the US-listed Chinese firms, but most of them aimed to be relisted in mainland China, expecting the potential easing of listing rules. However, the result was mixed. The regulatory reform was slow: until now, only the STAR and ChiNext (mainly for innovative startup companies) have adopted the new listing rule. As a result, a number of companies had to wait for a long time to get relisted.

This time, however, the more desirable place is Hong Kong. Before 2018, Hong Kong-listed companies were dominated by Old-Economy sectors, such as financial, property, energy, and consumer. The only well-known tech firm was Tencent. Due to its strict rules against weighted voting rights (WVR), Hong Kong Exchange (HKEX) missed a number of tech firm IPOs, such as Alibaba, in 2014.

Nevertheless, the 2018 listing regime reform by the HKEX has changed such narrative. Specifically, the new listing rules feature lower thresholds for biotech firms and approval of WVR structures; they also set up new listing rules for Greater China and international companies seeking secondary listings in Hong Kong.

Such changes are appealing for Chinese companies listed in the US by providing a new option to deal with the delisting threat. They are also appealing for companies seeking IPOs, especially for tech, healthcare, biotech companies.

As a result, the deteriorated relationship between the US and China and the more accommodative rules of the HKEX has encouraged more promising New-Economy firms to raise funds in Hong Kong (Exhibit 1.) and provided a significant boost for the fund-raising market to stay prosperous.

For the past two years, even with the global equity market downturn in 2018, and the social upheaval in 2019, HKEX still managed to secure its top IPO fund-raising status globally. However, the Chinese listings in the US slowed dramatically by 33% in 2019. Also, for the first half of this year, global IPO fundraising decreased by 18% compared to the same period of last year, but Hong Kong still managed to see an increase from USD 9.3 billion to USD 10.5 billion (KPMG). As the Ant group IPO approaching, Hong Kong Exchange should remain one of the top exchanges in IPO fundraising this year.

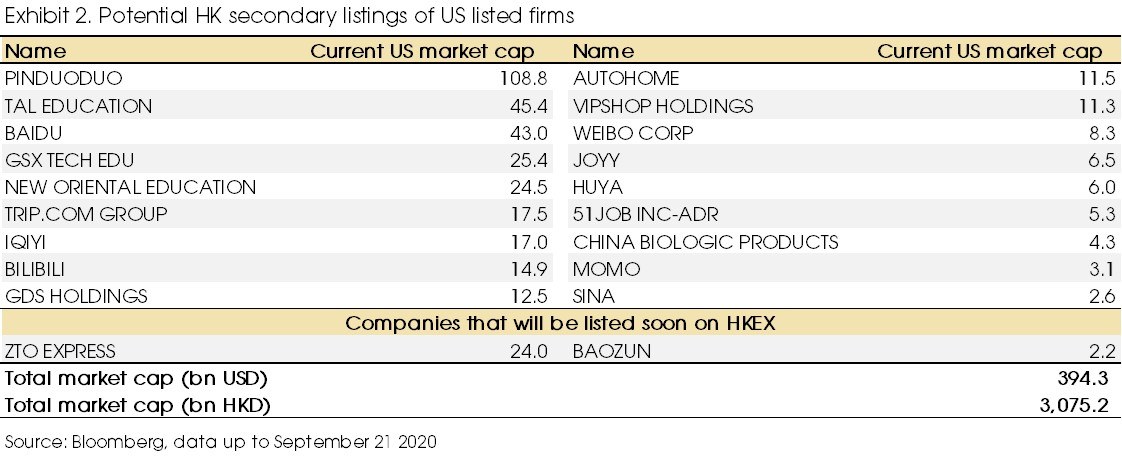

Currently, the total market cap of the Chinese firms qualified for secondary listings in Hong Kong is around HKD 3 trillion (Exhibit 2.). If these companies seek secondary listings in Hong Kong in the coming years, with 10% new share issuance, the estimated amount of fundraising could be HKD 300 billion.

Secondary listings could also bring back investors and funds from other markets to Hong Kong. For example, several of Alibaba's biggest investors have converted US ADRs into Hong Kong shares in part to avoid potential U.S. sanctions and de-listings. Temasek, Baillie Gifford, and Matthews Asia are among the major shareholders that have swapped the stakes (according to South China Morning Post). And we expect that more long-term fund managers, especially the ones based in Asia, are switching or considering to switch from ADRs into Hong Kong-listed shares.

Looking forward, we expect to see a continued increase in secondary listings as well as innovative-growth companies with weighted voting rights in Hong Kong, which would ultimately change the composition of the companies in the Hong Kong market by increasing the share of New-Economy sectors. Such potential changes could make Hong Kong more attractive to global investors.

Changing Landscape: Not A “Value Trap” Anymore?

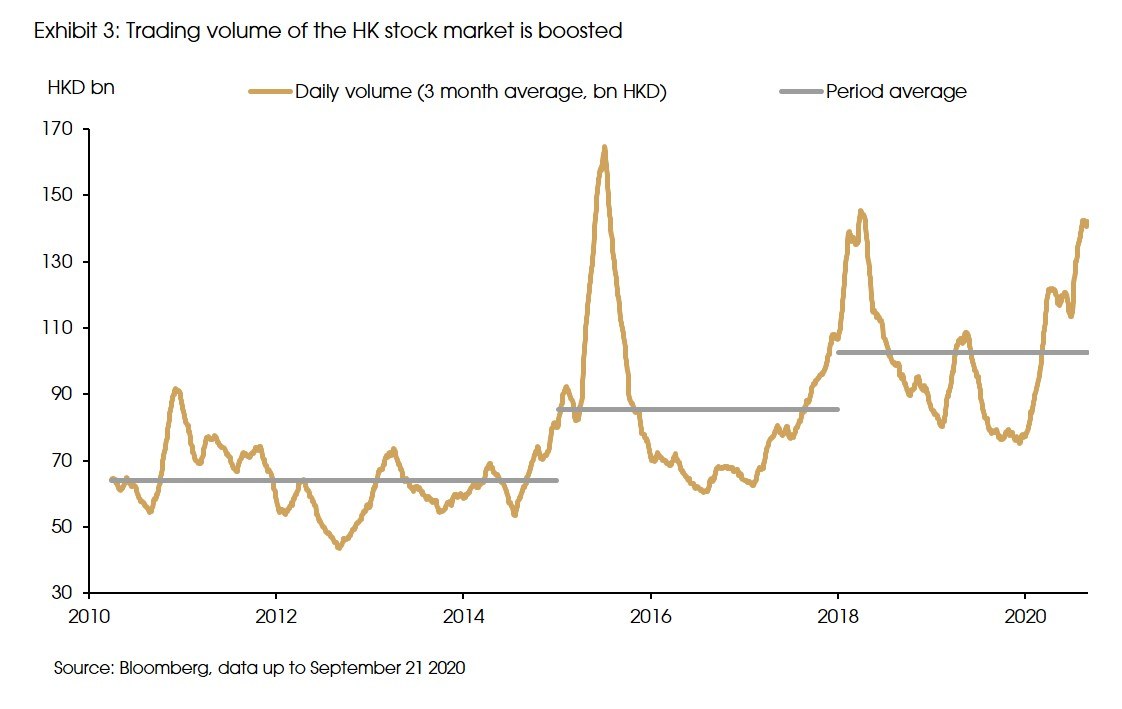

Despite the large market cap (Top 4 in the world), the trading volume and turnover ratio of the Hong Kong market is lower compared to other major stock markets. Therefore, a key question could be: whether these "coming back" secondary listings could get enough investors to trade their stocks in desirable volumes.

However, the relatively low trading volume is partially due to the Old-Economy dominated composition of the market. The increased representativeness of the New-Economy firms should attract more investors, promote tradings, and increase market liquidity.

Besides, Hong Kong has a large asset and wealth management industry. According to the Securities & Futures Commission (SFC), even during a time when global markets have been uncertain and challenging, and despite the social unrest and geopolitical tensions between the US and China, Hong Kong's asset and wealth management business still thrived last year, with a 20% year-on-year (YoY) increase in AUM to HKD28.8 trillion.

At the same time, assets managed in Hong Kong grew even faster by 24% YoY, from HKD 8 trillion to HKD 10 trillion. 52% of the assets under management are in equity. Hong Kong and mainland China are the most preferred markets for fund managers, representing 46% of the investment, and with mainland China seeing the fastest growth of interest (investments in mainland China increased by 48% last year). Such a large and steadily growing asset and wealth management industry and a stronger willingness to invest in China should provide a desirable pool of investors for the Hong Kong market.

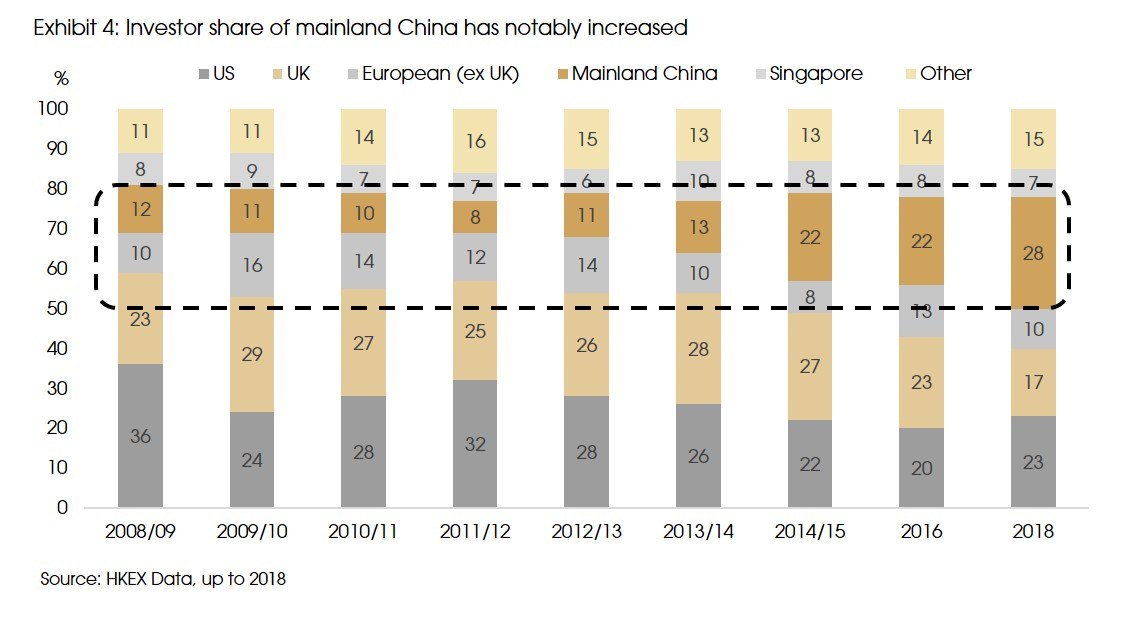

Moreover, the stock connect scheme launched in late 2014, and the changing composition of the listed companies have attracted more investors from mainland China, leading to a more balanced investor base.

The share of foreign investors has stayed relatively stable at about 40% in Hong Kong, previously dominated by the US and European investors (Exhibit 4.). Such dominance partially explains the notable influence of foreign central bank policies on the Hong Kong market and the hot money behavior, which increases market volatility. However, after the launch of the stock connect, the share of mainland China investors increased significantly from 10% before 2014/2015 to 28% in 2018, which could be a potential stabilizer of the market.

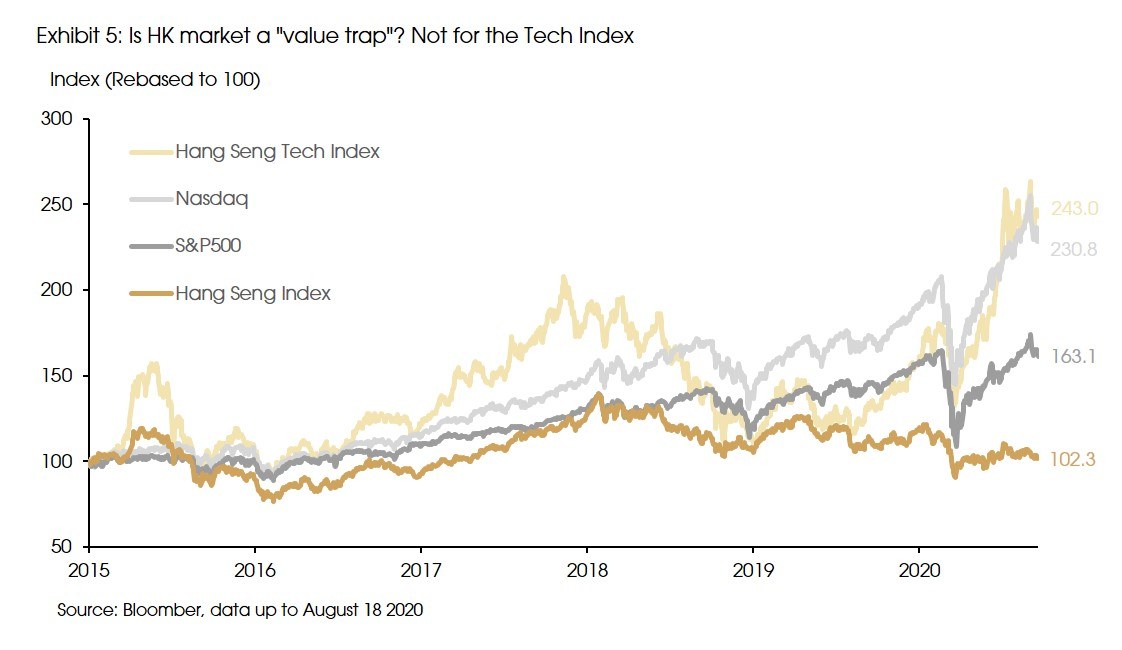

Finally, the Hang Seng index's PE ratio usually fluctuates between 9 to 13 and is now standing at around 12.9, which is low compared with most other markets (MSCI world at 19.4, MSCI-ACW, MSCI Emerging Asia 15.3). The Hang Seng Index's performance may look like a "value trap", especially compared with the performance of S&P500. However, the New-Economy heavy, Hang Seng TECH Index's performance is quite different, even better than the Nasdaq since 2015.

Before the Hang Seng TECH Index, the New-Economy sectors were under-represented in major indexes. The Old-Economy’s share in Hang Heng Index stands at about 70% even after the recent index rebalance, which is higher than that of the overall Hong Kong market (at around 56%). However, the Hang Seng TECH Index is dominated by New-Economy firms, with more than 80% of the components from the technology and healthcare sectors. The TECH Index's introduction could attract potential investors and funds seeking opportunities in the New-Economy sector.

Therefore, we expect that the changing landscape of more New-Economy firms and a more balanced investor base could help the Hong Kong market get rid of the "value trap" reputation by promoting trade, stabilizing market movements, and therefore, increasing valuation.

However, such an outlook is subject to risks, especially politically. For example, any ban on US funds from investing in Chinese IPOs or listings in Hong Kong, on top of the recent White House directive to the body in charge of overseeing billions in federal retirement savings to halt plants to invest in Chinese firms, is likely to hurt liquidity.

Rule of Law: From A “Cost and Benefit” Perspective

The National Security Law (NSL) has been implemented in Hong Kong for more than two months. And we are aware of the concerns among investors over a completely new law that bypasses Hong Kong's legislation institutions. However, based on our understanding of the Chinese central government's strategy towards Hong Kong, we want to make some clarification to ease the concerns over Hong Kong's judicial and economic independence.

The NSL aims to grant the Hong Kong government much stronger authority to intervene in actions that might jeopardize Hong Kong's stability. From a "cost and benefit" perspective, the Chinese central government balances Hong Kong's autonomy and social stability. After months of prolonged social unrest since last June, restoring Hong Kong's stability has become the top target, trumping the fear of international condemnation and sanction.

For the judicial system, according to Fu Hualing, Dean of Faculty of Law at the University of Hong Kong, the Basic Law remains Hong Kong's constitution by its nature, and Hong Kong courts could develop a common law jurisprudence in interpreting the NSL by the standards of the Basic Law.

The Chinese government indeed has the final interpretative power of the NSL, but it also has the final interpretative power of the Basic Law. And It does not mean that the Chinese government will frequently interpret NSL as it wishes. After all, the central government has only interpreted basic law five times since 1997 (Hong Kong requested three of them).

Moreover, so far, there still exits some essential trust between Hong Kong's judicial system and the central government. In the first draft of the NSL, Hong Kong's pro-establishment group endorsed the forbiddance of foreign judges to handle NSL related cases, and also the Chief Executive's (CE) authority to select judges for NSL related cases. However, the final version of the NSL rules out the specification of banning foreign judges and also adds the arrangement that the CE might refer to the Chief Justice for judge selection.

Therefore, for now, we have faith in Hong Kong's Judiciary, and we believe the Judiciary would not remain silent towards any actions that might be detrimental to its independence.

For the economic system, Hong Kong enjoys a much more autonomous status compared with its political system. Internationally, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and SFC enjoy a parallel position as the China Securities and Regulatory Commission. Moreover, the Chinese central government helped to persuade Ashley Ian to stay for another term as the CEO of the SFC to enhance investors' confidence on Hong Kong's financial market after the pass of the NSL, showing that the central government has no intention to intervene in Hong Kong's economic system at the current stage.

Indeed, in the worst-case scenario, China could terminate the one-country-two-system. However, terminating Hong Kong's own system gets China little benefit but will generate tremendous cost.

Hong Kong is not replicable, given China's relatively closed financial system. The capital flow among international financial markets, the Hong Kong market, and the Mainland China market have been operating well for decades. Any disruption on such chain will cost huge unintended costs for China.

Sources: Harvard Business Review, Financial Times, KPMG, South China Morning Post, HKEX, CICC