CIO Viewpoint: Eurozone Bumpy Optimism

Deepest Recession in Decades, Bumpy Recovery Ahead

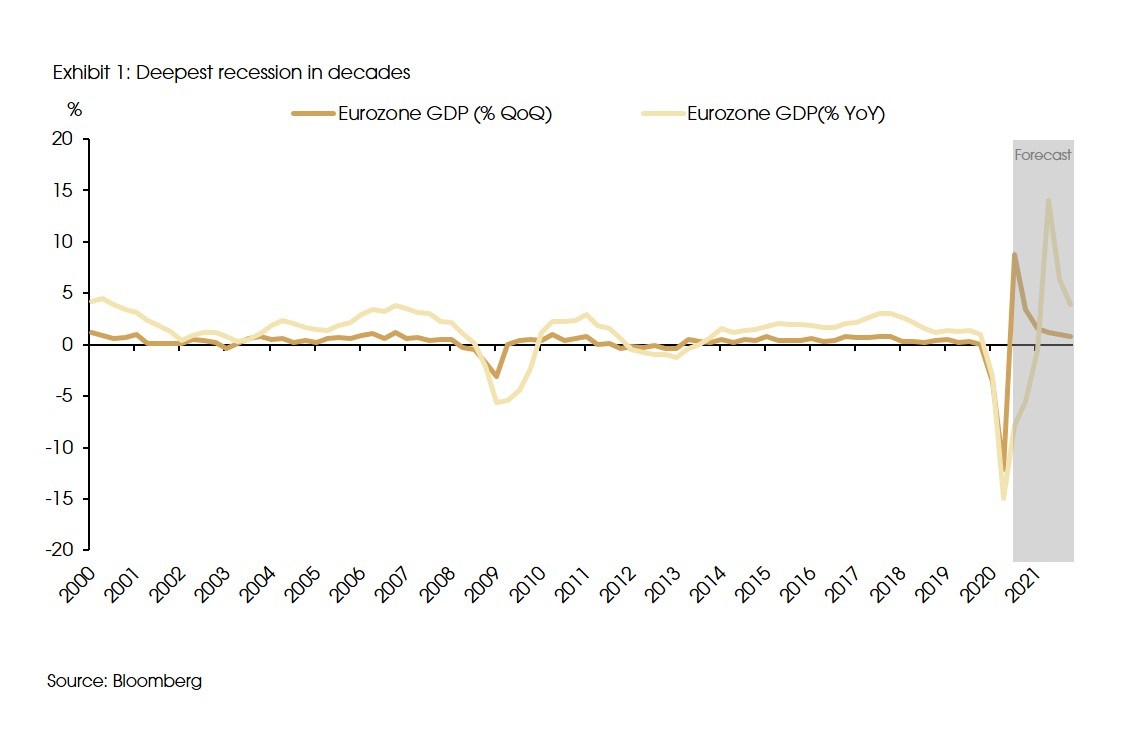

The outbreak of Covid-19 has resulted in large scale containment measures globally and dragged major economies into the deepest recessions since 1930.

In the euro area, economic growth turned negative since the first quarter. The weakness of the economy was broad based: private consumption in Q1 took the biggest hit and decreased by -4.7% qoq, followed by investment expenditure, declining by -4.3% qoq. Government consumption also declined, but at a much milder pace (-0.4% qoq). Exports fell more significantly than imports and inventories started to pile up.

For the second quarter, the headline data suggested one of the deepest recessions for the euro area in decades, with GDP decreasing by -15% yoy (-12.1% qoq). According to market forecasts, all components are expected to have record falls with the exception of government consumption, as a number of fiscal stimulus were implemented by governments to fight against the economic damage created by the pandemic. Furthermore, capital investment is expected to be hit harder in 2Q, as lockdowns spread from shops and restaurants to factories.

Differences across countries is largely attributed to the different timing of harsh lockdowns and containment measures, as well as each countries dependence on tourism and services.

Sectors with the largest declines include trade, transport, accommodation and food services as well as arts, entertainment and other service activities, while agriculture, forestry and fishing, together with financial and insurance activities saw relatively milder declines.

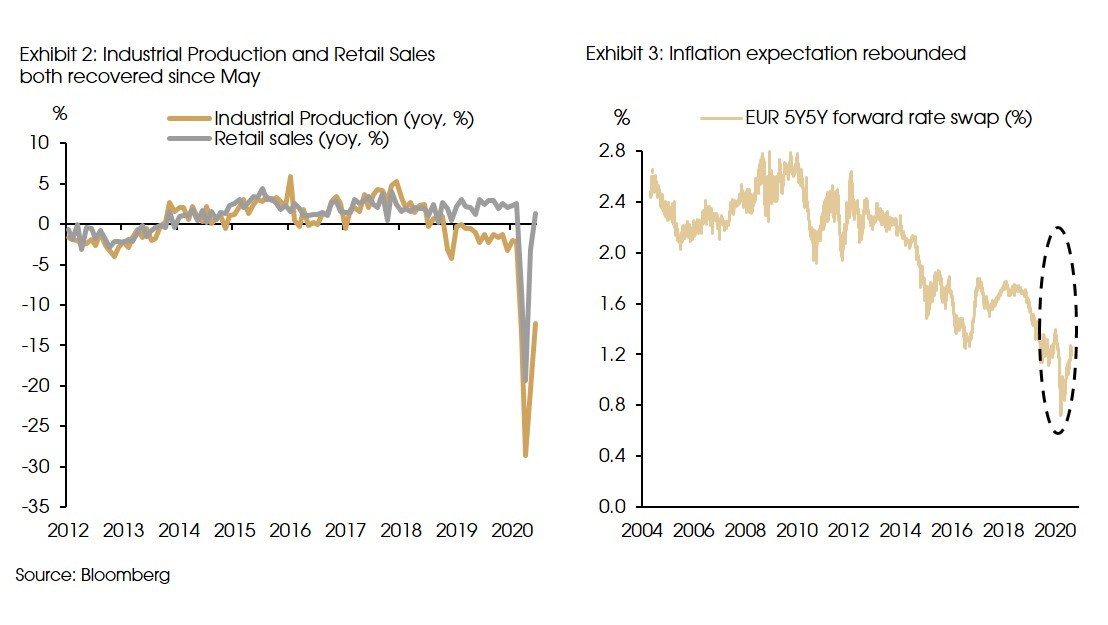

Looking forward, as lockdown measures are gradually lifted, the expectations of an economic turnaround in the second half of the year for the euro area are increasing. Specifically, recent economic data such as industrial production, retail sales and sentiment indicators are all showing improving trends. Inflation expectations seem to have also picked up.

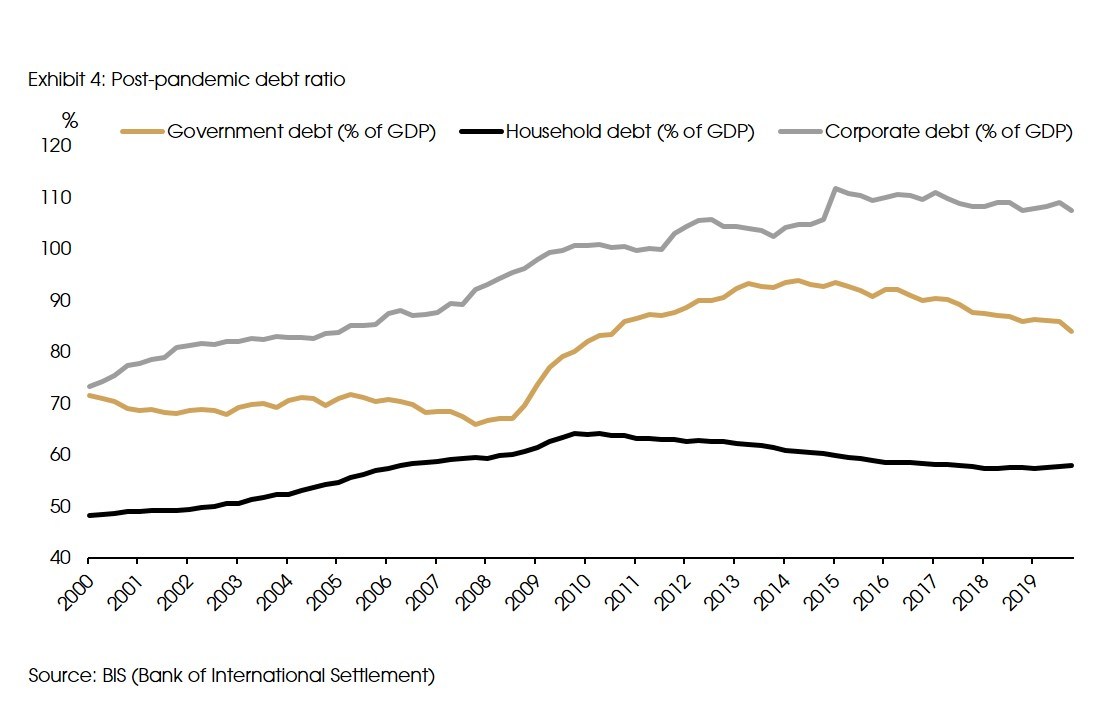

We expect the recovery of consumption to be faster than investment. Specifically, the corporate sector’s balance sheet has generally deteriorated during this deep recession. Thus, before significant improvements on economic outlook and corporate cash flow, we do not expect to see a notable rebound in capital investment. Indeed, the bank lending growth significantly increased since March, but it is more likely to be driven by emergency liquidity needs and liquidity support measures, such as the drawing of credit lines and phasing in of government guarantees. The recent increase in bank lending is unlikely to signal a pickup in corporate investment activity.

However, for the household sector, government allowances have increased disposable income and savings. In addition, the household sector’s balance sheet was much healthier than the corporate sector (reflected by a lower debt ratio). We expect to see a relatively faster recovery of consumption and the housing market versus capital investment.

Although the uncertainty regarding economic reopening remains high, when looking into recent data we still see an overall improving trend for the region’s economic activities. According to the European Committee’s forecast, Euro area growth will drop from 1.3% in 2019 to -8.7% in 2020 before seeing a rebound of 6.1% in 2021.

Risks are Balanced to The Downside

A severe resurgence of the pandemic could force countries to re-impose massive containment measures, and reverse the improving trend. August PMI data fell short of expectations as the increase of new Covid19 cases among European countries dampened business sentiment. Moreover, the resurgence of the pandemic seems unavoidable before any effective vaccines or therapy are available.

In addition, certain demands are hard to recover in the short run, for example, cross-border traveling and the pandemic has inflicted high costs on firms, lowered their revenues and worsened their profit outlook. Therefore, we may see more corporate defaults especially for the most affected sectors and for the most indebted corporates, where initial liquidity strains could turn into solvency problems.

A rise in corporate defaults could have further knock-on effects on employment. Such vicious cycle between corporate stress and unemployment could amplify and lengthen the pandemic shock. It could also raise non-performing loans and negatively affect banks, particularly for those with high exposures to pandemic-sensitive sectors or the hardest hit countries.

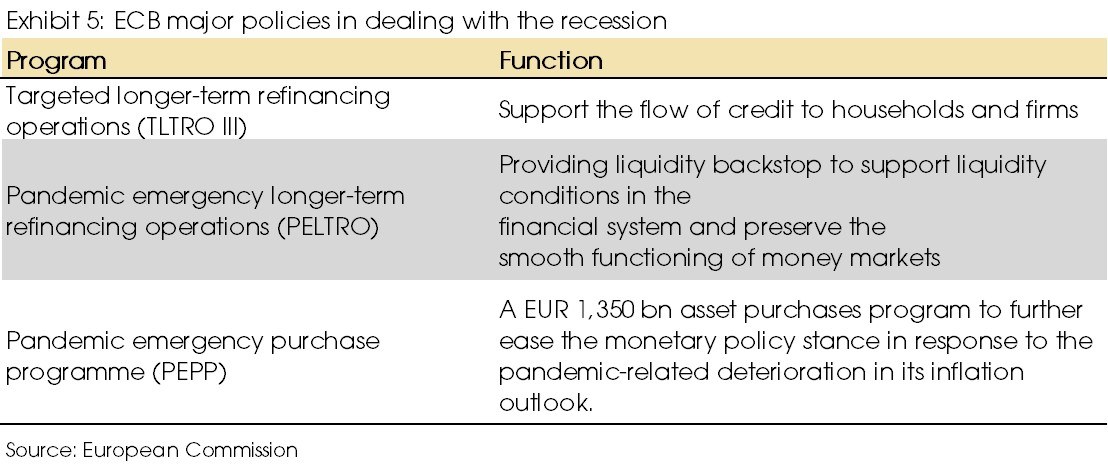

Monetary Policy will Remain Supportive

In light of signs that the euro area is facing an unprecedented economic contraction, the ECB has announced additional monetary policy easing measures in recent months to ensure a necessary degree of monetary accommodation and a smooth transmission of monetary policy across sectors and member states. This includes measures such as liquidity enhancing to support the flow of credit to households and firms as well as providing an effective backstop to support liquidity conditions in the financial system.

The Bright Spot: The Launch of The Recovery Fund

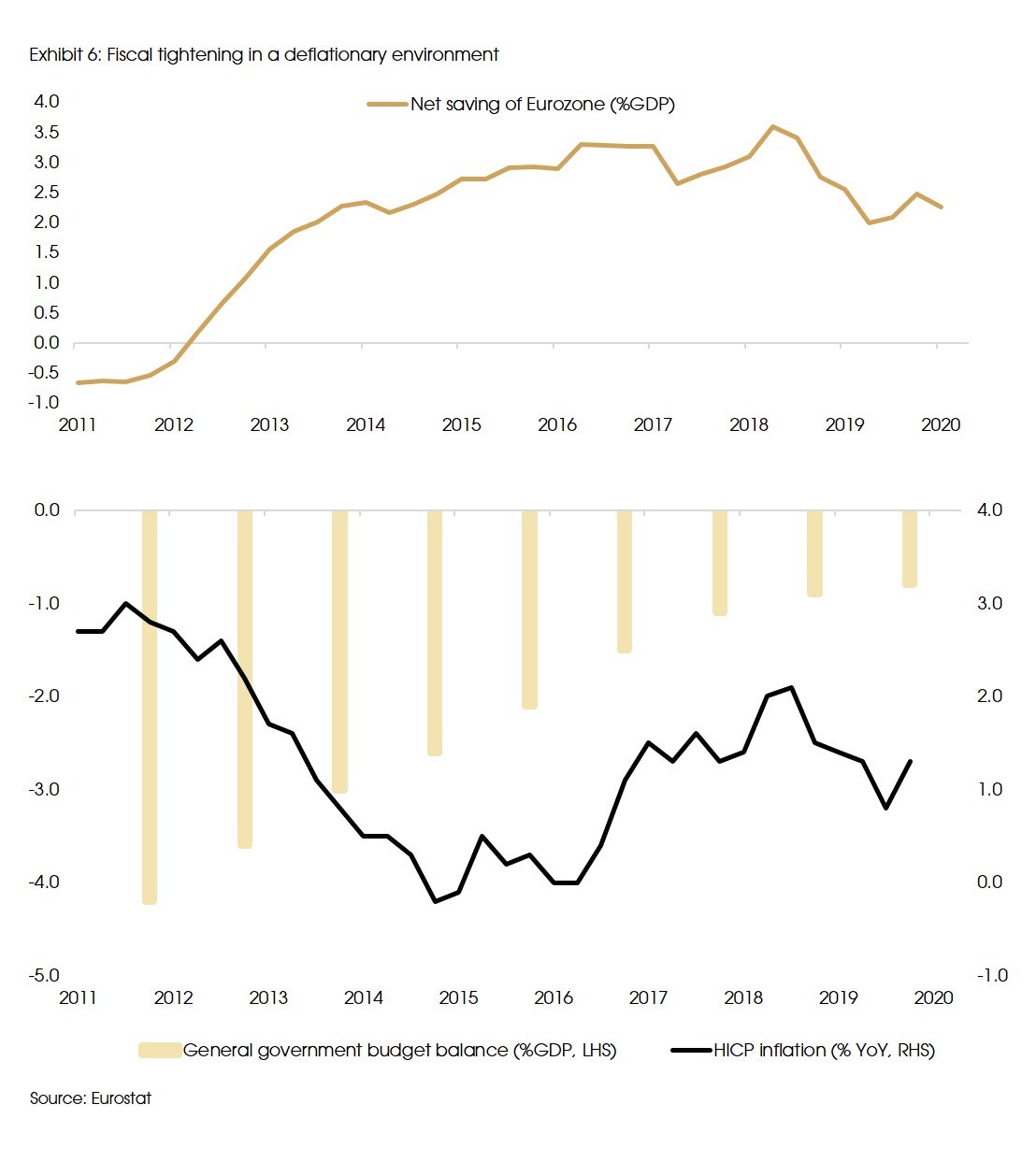

For the past decade, the Eurozone economy has been stuck in a liquidity trap, where aggregate demand was inadequate, private sector savings were abundant and inflation pressures have been muted, even though the ECB has kept the benchmark interest rate below zero. Such situation requires expansionary fiscal stance to increase aggregate demand and boost inflation.

However, for a long time, fiscal conservatism has dominated the thinking of EU policymakers, particularly the “frugal four” (Austria, Sweden, Netherlands, and Denmark) and Germany. Fiscal prudence may seem “sound” from a public policy standpoint, but it may intensify deflationary pressures when the underlying economy is struggling with inadequate demand.

The final deal of the recovery fund is a major step in the right direction. The package is not only large enough to be economically meaningful, but also an indication that member countries are committed to multilateralism, or a more united EU.

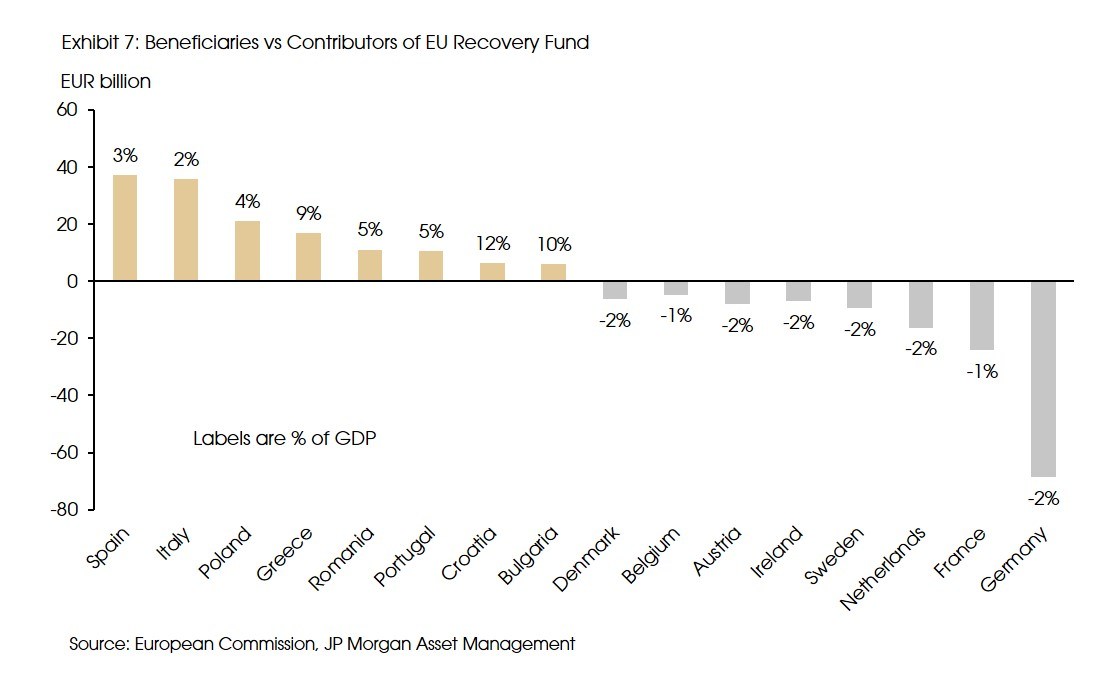

52% of the EUR 750 bn recovery package (~5% of GDP) will be grants and the rest are loans. It is expected to be financed by large issuance of joint EU bonds and serviced by the EU budget.

More important, the funds will be allocated to member countries on a “need” basis (allocation key takes into account population, GDP per capita and unemployment). Countries that are most affected by the crisis will benefit the most.

It also means that high-debt countries, such as Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece will not only receive more funds but also at a lower borrowing cost, as these funds are financed by the European Commission’s AAA rating, instead of by their own ratings which in some cases can be lower. The southern European countries’ high sovereign risk premia have greatly aggravated their debt burdens and suffocated their economic growth. However, with a pan-European bond, borrowing costs in these countries will be lowered significantly.

According to the European commission’s report, the recovery fund could help the vulnerable countries to stabilize their banking system by shrinking risk premia in southern Europe, which should be helpful for many weak lending institutions. Thus, such fiscal action together with monetary measures could possibly prevent large-scale bankruptcies within the region.

Implications on Euro Bonds and The Euro: A Potential Safe Asset

Prior to the launch of the recovery fund, EU bonds were but a small part of the marketplace. Looking forward, the EU will have to issue significant amounts of debt, or joint EU bonds, to fund the package, and that could probably create some real European safe assets.

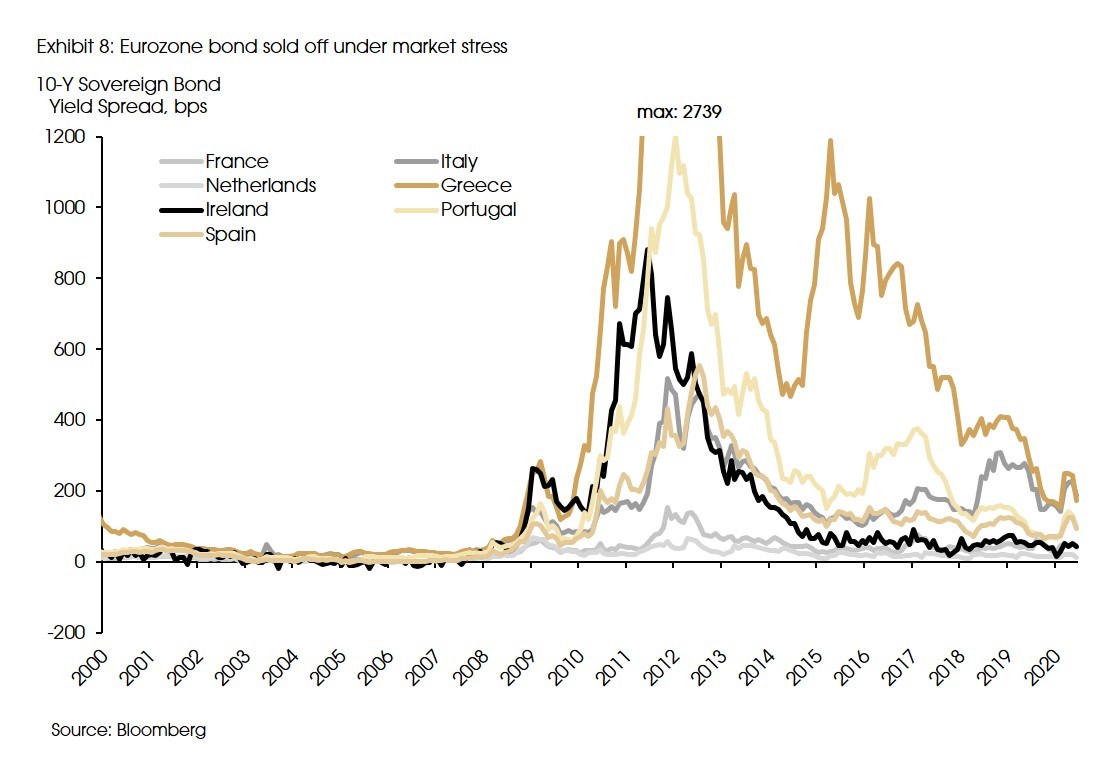

For years, the huge aggregate euro area government bond market was only like a collection of fragmented individual sovereign issues – despite a common central bank. Given the substantial differentiation in sovereign credit risks across the euro area, the eurozone sovereign bond markets looked more like a group of “municipal bond markets” with distinct and variable credit and liquidity premiums, especially in times of market stress. The Greek debt crisis and the Italian government bond upheaval in 2018 are good examples emphasising such issues.

Therefore, backed by the European commission’s AAA rating as well as the EU budget, the new joint EU bond will have a much better depth and liquidity profile, which will lend more backing to the euro, and could potentially become a new safe asset.

Equity Market: Cyclical Stocks could Catch Up

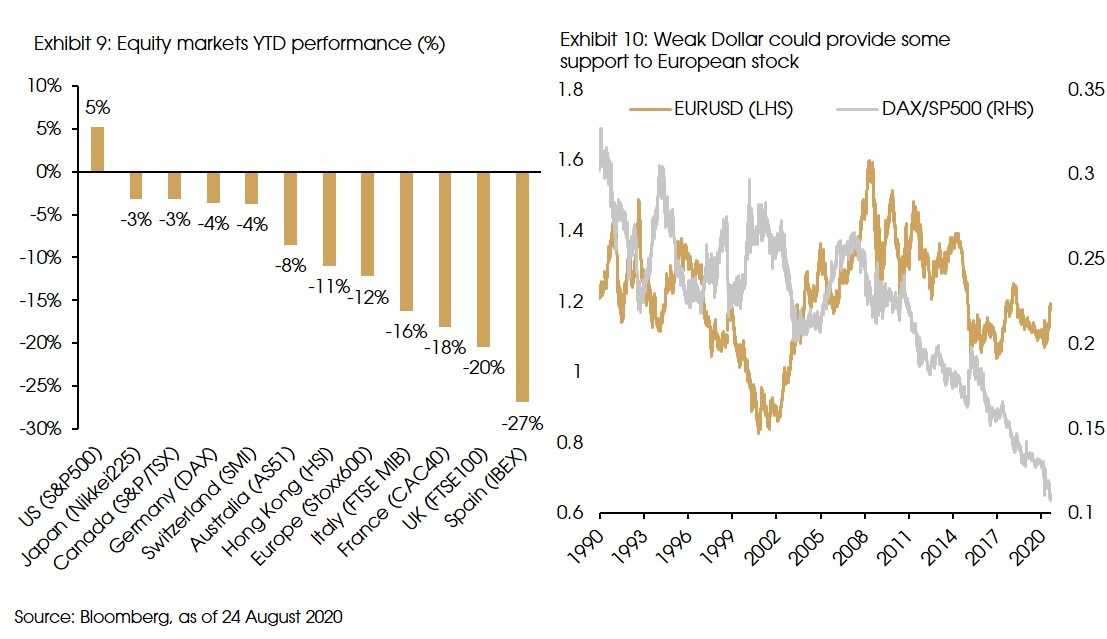

Historically, European stocks are sensitive to cyclical swings in the global economy. This is somewhat related to the fact that most European equity indexes have a fairly high concentration in cyclical sectors, such as financials. So far, technology and the so-called COVID-19 winners have led the rally in global stocks this year, whereas markets with a high concentration into cyclical sectors have lagged.

Nevertheless, the market leadership will likely shift as the global economic recovery continues to broaden in 2021. A potential recovery boom next year would require a continued improving economic growth rate. A potential effective vaccines could further lift the return to economic normalcy for most parts of the world. Cyclical stocks and European equities should do well, at least for a period.

Another factor that is favourable to European stocks is the dollar weakness. Historically, the performance of European equities relative to the US is generally negatively correlated to the dollar strength.

US-China Conflict: Will It Benefit The Eurozone Economy?

The new combative relationship between the US and China has changed the global commercial landscape and disrupted supply chains. Overall, in terms of global trade growth, it has caused a net loss for the world’s economy. But regionally, the deteriorated trade relation between the biggest countries did shift orders away from China and the US to alternative suppliers.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has shown that the EU, together with Taiwan, Mexico and Vietnam, have picked up some of the crumbs. As China’s exports declined by around USD 25bn in the first half of 2019, the EU exported an additional USD 2.7bn to the US, with the highest proportion in machineries sectors.

Even a smooth “phase one” trade deal between the US and China, could still be beneficial for the EU. Other than buying US products, the “phase one deal” also includes laws which focus on fairer treatment of foreigners, opening-up some of the financial sectors to foreign investment and protections for intellectual property. Therefore, the forced technology transfers have been outlawed, ownership limits on pension management and life insurance enterprises have been relaxed, and if these rules are effectively enforced by China in the future, then it will benefit all foreign companies operating in the country.

The most recent escalation of the trade tension is the new sanctions on Huawei.

The ban has been bad for vendors of US technology into China, but it has also left the EU and its companies in a “tricky” position, as illustrated by the diplomatic fallout from the UK’s Huawei 5G decision.

Sources: European Commission, JP Morgan, Financial Times, BlackRock