Focus: Where is my PlayStation 5? - Breaking Down the Global Semiconductor Shortage

Rensi Widjaja

If you are an avid fan of the PlayStation 5, like some of our colleagues here in the office, lately it has been increasingly difficult to get your hands on this highly anticipated game console. In recent months, there has been a long wait time for consumers wanting to buy cars and electronic products starting from personal computers to game consoles, and home appliances such as refrigerators, smart TVs and even toasters. The common denominator? Inside these products are thousands of microchips which enables them to function. These chips have been in a massive scarcity since the beginning of 2020 and as a result many automobiles and popular consumer electronics are in short supply.

As with many other aspects in the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has had massive impact to the semiconductor industry affecting many end markets. The supply chain disruption in the semiconductor industry has caused major companies to halt production lines and lay off thousands of workers globally.

For this month’s focus, we will try to breakdown the ongoing supply chain shortage, understand what caused the phenomenon to happen, its implications as well as where we see opportunities going forward

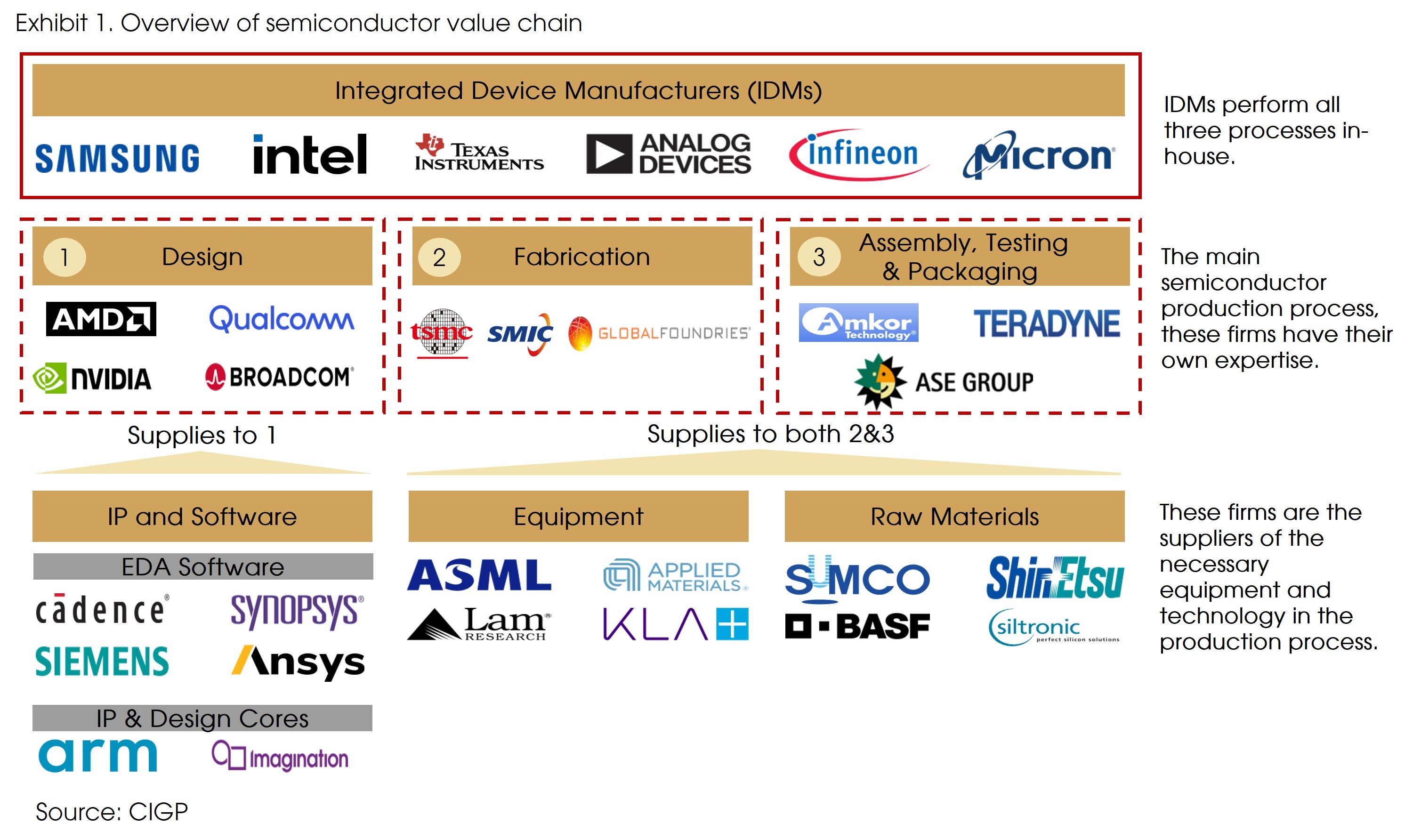

Understanding the semiconductor supply chain

The semiconductor industry’s supply chain is a highly integrated and globalized one, with the production process of these chips often being executed in multiple different countries before being finished and ready to distribute or used.

For example, a European firm licenses the IP on the processor cores, but it will be designed by a US fabless design company, manufactured by a Taiwan foundry, packaged by a Japanese company, to be used in a US smartphone. This value chain relies on the collaboration and trade between key countries and region, including the United States, Taiwan, China, Japan, Europe, and South Korea. Due to its interdependent nature, the semiconductor industry is susceptible to geopolitical risks, bottlenecks, and supply shocks.

The semiconductor industry is well known for its cyclicality of boom-and-bust cycles with upturns in the sector signaled by periods of low inventory and high influx of demands. This was the case with what we see during the 2000 dotcom bubble and 2016-2017 period when increased usage of smartphones and cloud computing drive demands for chips.

What happened?

The current semiconductor shortage is commonly understood to be a byproduct of the pandemic that disrupted various supply chains globally. While this is true, there are however other variables than what meets the eye. In order to better comprehend the ongoing situation, it’s important for us to take a step back and understand the dynamics within the industry prior to the pandemic.

China’s Deteriorating Auto Sales

The year of 2019 saw the semiconductor industry experiencing new highs propelled by increasing demands from 5G roll out. This in turn started to create pressure in chips supply well before the pandemic went full blown.

Going into 2020, China, the world’s largest auto market, has been experiencing a two-year slump in its auto sales. According to China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, total car sales in China fell by 8.2% to 25.8 million units in 2019, after a 3% dip in 2018. This was the first contraction observed since the 1990s with 18 months straight of declines. When the pandemic happened, auto sales further dropped significantly by almost tenfold in February 2020.

As the economy slowed down and outlook dimmed, to conserve cash, automakers slowed down their chip purchases. Concurrently, the world pulled to a stop and the work from home era triggered an increase in demand for electronics such as PCs, notebooks, TVs, gaming consoles, etc. The result? Priority shifts and chips manufacturer reallocated orders from one end market to another.

However, In the third quarter of 2020, vehicle sales and orders rebounded faster than expected, and automakers rushed to ramp up production to meet demand. Things then became tricky as chip manufacturers have committed large orders to the companies benefitting from COVID tailwinds.

The semiconductor supply chain is a highly complex global ecosystem involving a lot of moving parts. The lead time to manufacture a single chip takes a relatively long period of time (approximately 6 months) and once the process starts, the massive upfront costs make it impossible for factories to implement alterations.

As such considering the dynamics of the auto market prior to the pandemic, when COVID-19 happened, it created a snowball effect that would go on to affect many end users. Major auto OEMs and electronics makers then experience delays in manufacturing, unable to secure chips for their products as foundries run in full capacity.

Impacts from US China Trade Sanctions

Another piece of the puzzle was the impact from the US-China geopolitical tensions. US trade sanctions prohibit the sale of US semiconductors technology including IP of chip designs to the Chinese tech behemoth, Huawei.

Afterwards, hoping to ensure the continuity of its business operations, Huawei started to build large stocks of chip inventories. The company reportedly managed to secure two years’ worth of productions by mid-2020. Other companies soon followed suit as the Chinese tech industry is still highly reliant on US manufactured chips.

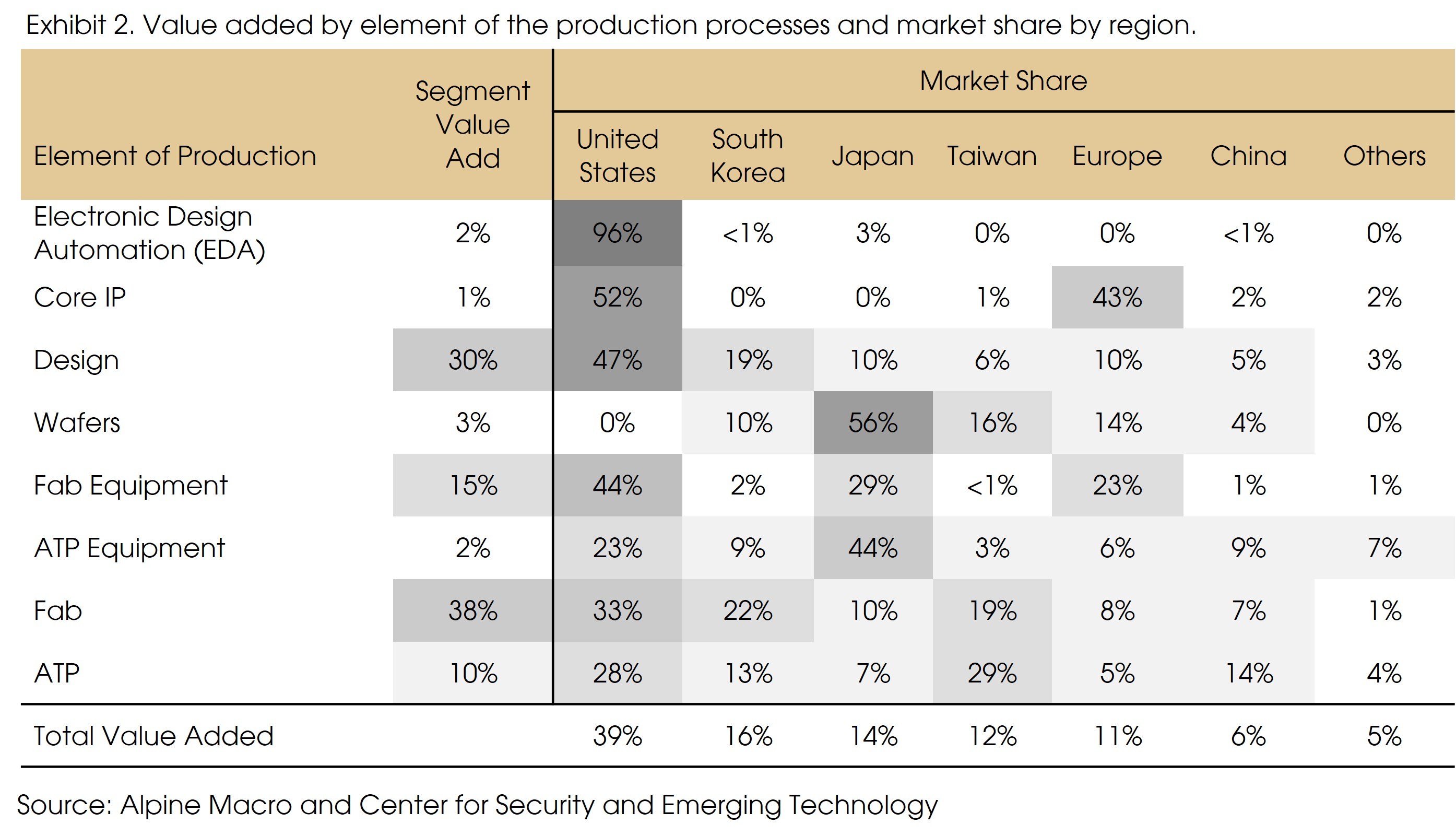

US companies controls about 90% of EDA (Electronic Design Automation) market share globally. This includes the design IP for companies such as Apple, Samsung, Qualcomm, Nvidia, Micron and Huawei.

It was reported that in 2020, China’s import of chips climbed to almost USD 380 billion, which was up from USD 330 billion the previous year.

Natural Disasters and the Delta Variant

To make matters worse, several one-off catastrophic events happened in major semiconductor factories in Japan and Texas has brought further hiccups to chip manufacturing.

Renesas Electronics who is a major provider of global automotive chips, was damaged by fire in March, disrupting production for months.

Meanwhile, Samsung, the South Korean Integrated Device Manufacturing (IDM) powerhouse was forced to shut down its Texas plant for over a month in February 2021 as storms caused power outage in the area.

The Samsung Texas plant is a production center for microprocessors like radio frequency integrated circuits and solid-state drive controllers. Samsung reported the month-long halt to have impacted a total of 71,000 wafers which worth about USD 250 – 300 million in value.

The resurgence of COVID-19 variants in countries such as Malaysia and Vietnam have also exacerbated the issue further as factories were forced to shut down. Both countries are major centers of semiconductor packaging and testing facilities.

What are the implications?

According to Goldman Sachs, semiconductor manufacturing constitutes only about 0.3% of US GDP, however they are critical supplies to 12% of the US economy where they depend on and implement semiconductors in their products. It is estimated that approximately 169 US industries are affected by the shortage.

Globally, the Washington Post reported that chip shortages are expected to wipe out USD 110 billion of sales for carmakers this year, with production of 3.9 million vehicles lost. Broadband providers in Europe were facing delays of more than a year when ordering internet routers. Apple mentioned supply constraints are affecting the sales of iPads and Macs. The company said that the supply crunch has taken off about USD 3 billion off its Q3 2021 revenue.

To address the current issue at hand, chip manufacturers have been trying to ramp up their production with foundries and manufacturers increasing their capacity by the end of 2021. During its earnings call in July 2021, TSMC communicated that the company will ramp up production of microcontrollers by close to 60% over 2020 level. This is expected to boost supplies for its auto clients starting from Q2 2021.

One of the most important spillover effects of the supply chain shortage has been on the impact to prices of semiconductors chips that have been climbing since late 2020. As the supplier of over 90% of the world’s advanced semiconductor chips, TSMC has also recently announced its intentions to increase prices of most its advanced chips by 10% and 20% hikes for less advanced chips.

This is reported to be the biggest price hike seen in over 10 years. We expect this to result in inflationary pressure for most of end market users which will most likely be passed on to consumers. The hike in price for semiconductors is expected to take into effect late in 2021 or early 2022.

Creating a more balanced global supply chain

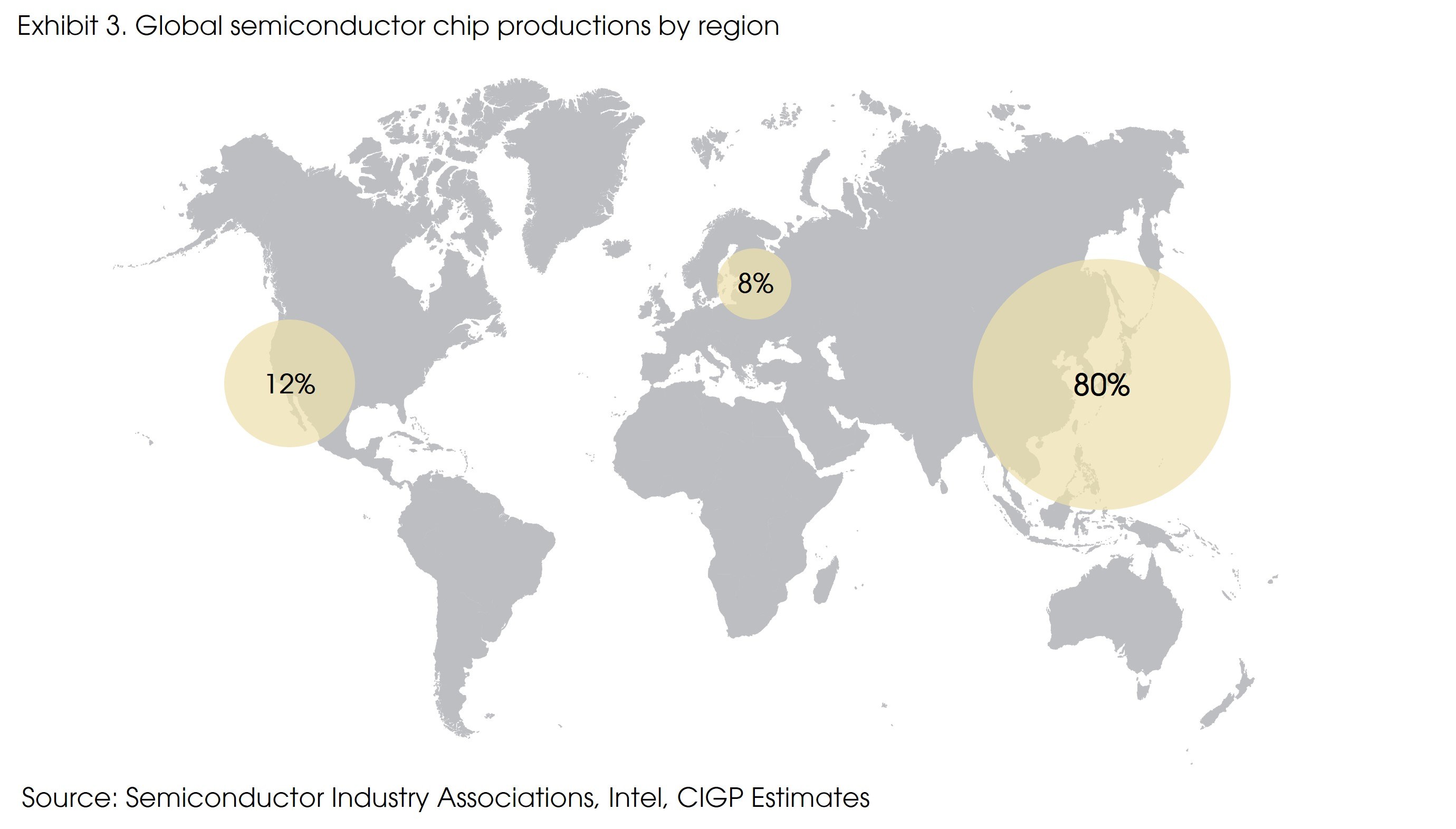

The COVID-19 pandemic has in particular exposed loopholes in semiconductor manufacturing. Currently, about 80% of the world’s most advanced technology leading manufacturers are heavily concentrated in Asia as seen in Exhibit 3. Global governments have taken serious measures to reduce over reliance in one region, with the hopes of domesticating the semiconductor supply chain by introducing bills that support in-country production.

According to the Semiconductor Industry Association, the share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity in the US has decreased from 37% in 1990 to about 12% today as the US lags other countries in federal investments within the sector. This issue has been one of President Biden’s key economic agenda as he looks to return chip manufacturing leadership to America.

The recent CHIPS for America Act passed by the US Senate aims to support and provide financial incentives and subsidies for semiconductor companies to build and expand manufacturing capabilities in the US and provide funding for specific semiconductor programs. The bill could potentially allocate as much as USD 50 billion with expected distribution timeline as soon as Q1 2022.

Over in the EU, political leaders have been quite vocal in their ambitions to establish tech sovereignty for semiconductor manufacturing, amongst other areas. The European Commission officials have recently hinted on a “European Chips Act” that is targeted to support 3 core areas in semiconductor supply chain: bolstering research, increasing production capacities, and expanding wider international ties to create a more diversified supply chain.

With this, the EU bloc is looking to increase the region’s chip production to approximately 20% of the global market by 2030 with the assistance of major players such as TSMC, Intel and Samsung. All of which have considered themselves to be an important player to alleviate supply chain risks by opening manufacturing plants in the US and Europe in an effort to create a more balanced global semiconductor supply chain.

What’s next?

All in all, despite massive efforts from governments and foundries, many large industry players expect shortages to continue to persist to 2023 as major investments by companies and governments to extend manufacturing capabilities will most probably take a considerable amount of time to be fully realized. Hence it is rather difficult to say exactly when the supply crunch will subside.

Tying in all aspects together, we believe that the current semiconductor supply shortage brings attractive opportunities for players in the industry that hold high competitive moats.

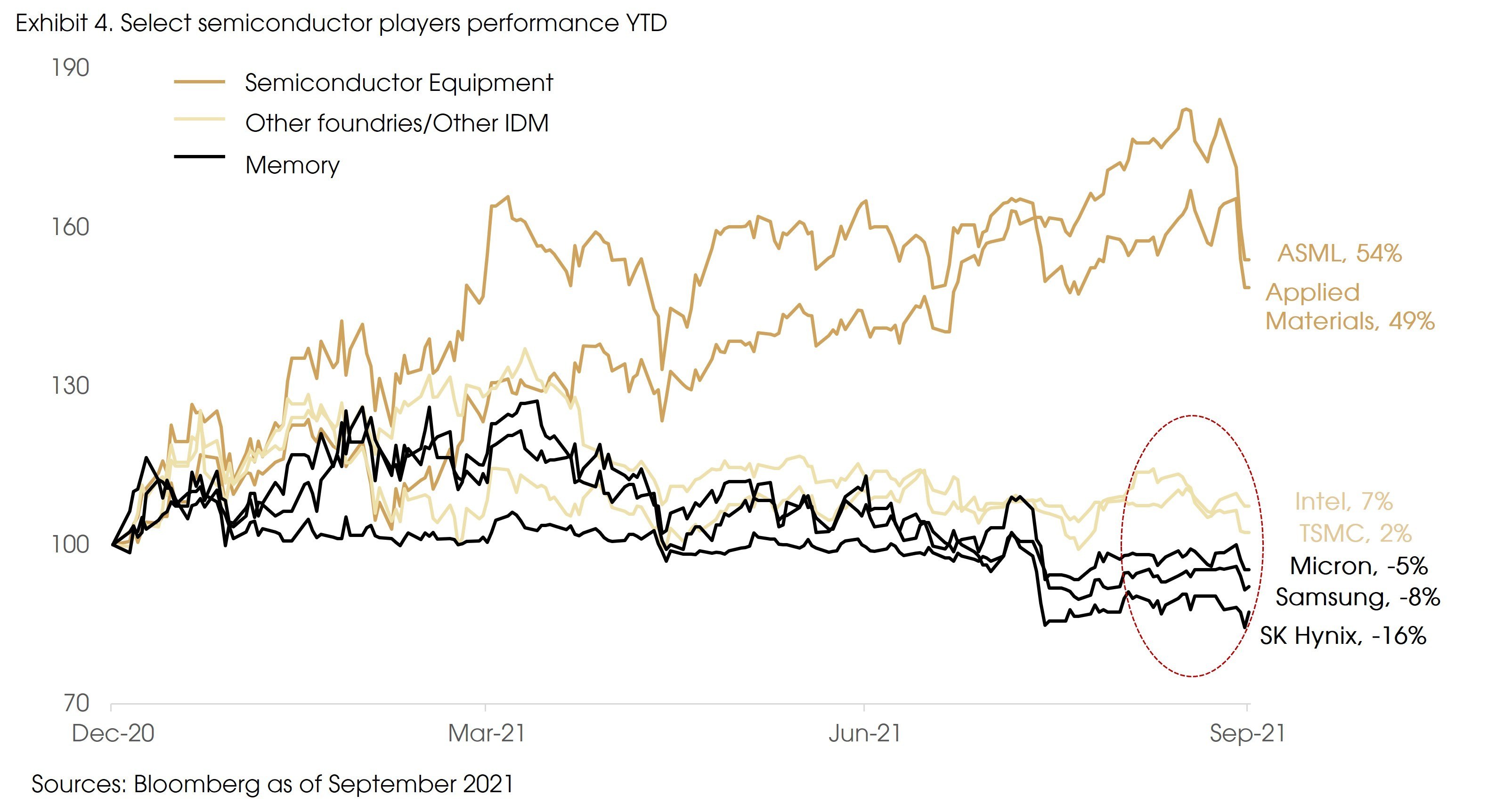

Within the short term, on the back of continued strong demand growth outlook across areas, including Cloud, Data centers and PCs we believe it will continue to be favorable for certain foundries players. Despite the extensive capex plans within the next 2-3 years that will potentially dampen earnings growth, considering recent price hike decisions, we think it might somewhat be able to offset the negative impact. We further note that Memory’s YTD performance has been relatively muted compared to other semiconductor peers (See Exhibit 4). Over the long term, we think semiconductor capital equipment players are well positioned to be prime beneficiaries of the current phenomenon as manufacturers ramp up their productions hence triggering demand for equipment makers.

Sources: Bloomberg, Financial Times, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Washington Post