CIO Viewpoint: Which is more impactful in 2022 - higher inflation or moderating growth?

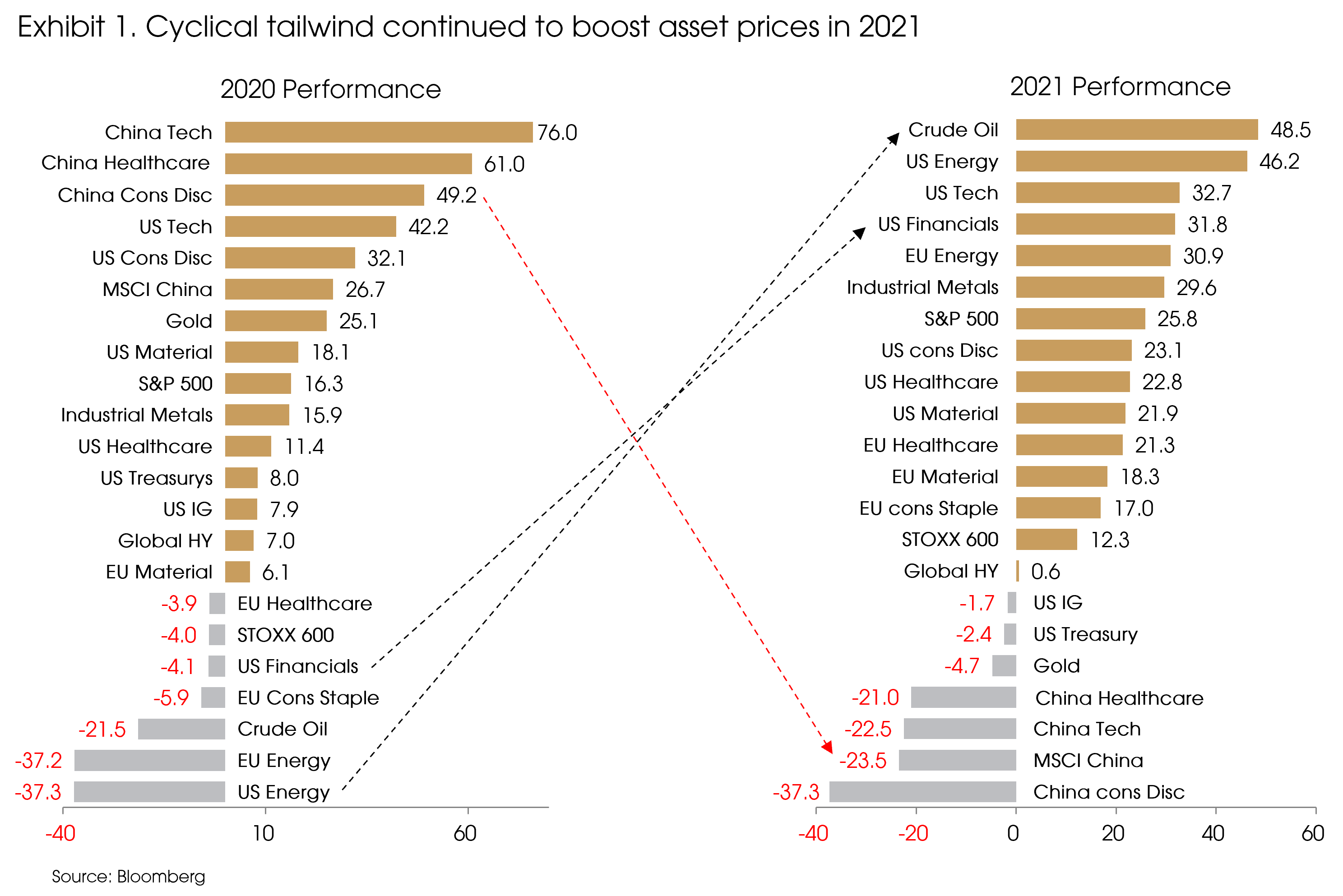

2021 has seen a V-shaped recovery in major economies, which led to rising interest rates and higher inflation. Such a macro backdrop supported the performance of risk assets, especially cyclical assets (Exhibit 1). For example, crude oil and energy stocks were the best performing assets in 2021. Other cyclical assets/sectors also did well, such as financial names and industrial metals.

However, there have been several rotations behind the overall trend.

At the beginning of the year, the USD 1.9 trillion pandemic relief package brightened the demand outlook, leading to reflation trade in the market. Cyclical assets significantly outperformed.

However, during 2H 2021, with the expiring US stimulus packages and China’s credit tightening, policy support declined and growth moderated. Meanwhile, supply bottlenecks persisted due to the new waves of the pandemic, and the green transition exacerbated energy shortage, leading to surging upstream prices. Therefore, the reflation trade turned into stagflation concerns. As a result, cyclical assets fell, while growth names regained leadership and energy names remained strong given the rising prices.

Moreover, emerging markets underperformed as multiple resurgences of the pandemic posed greater concerns. The dramatic correction of the Chinese market also contributed to this underperformance.

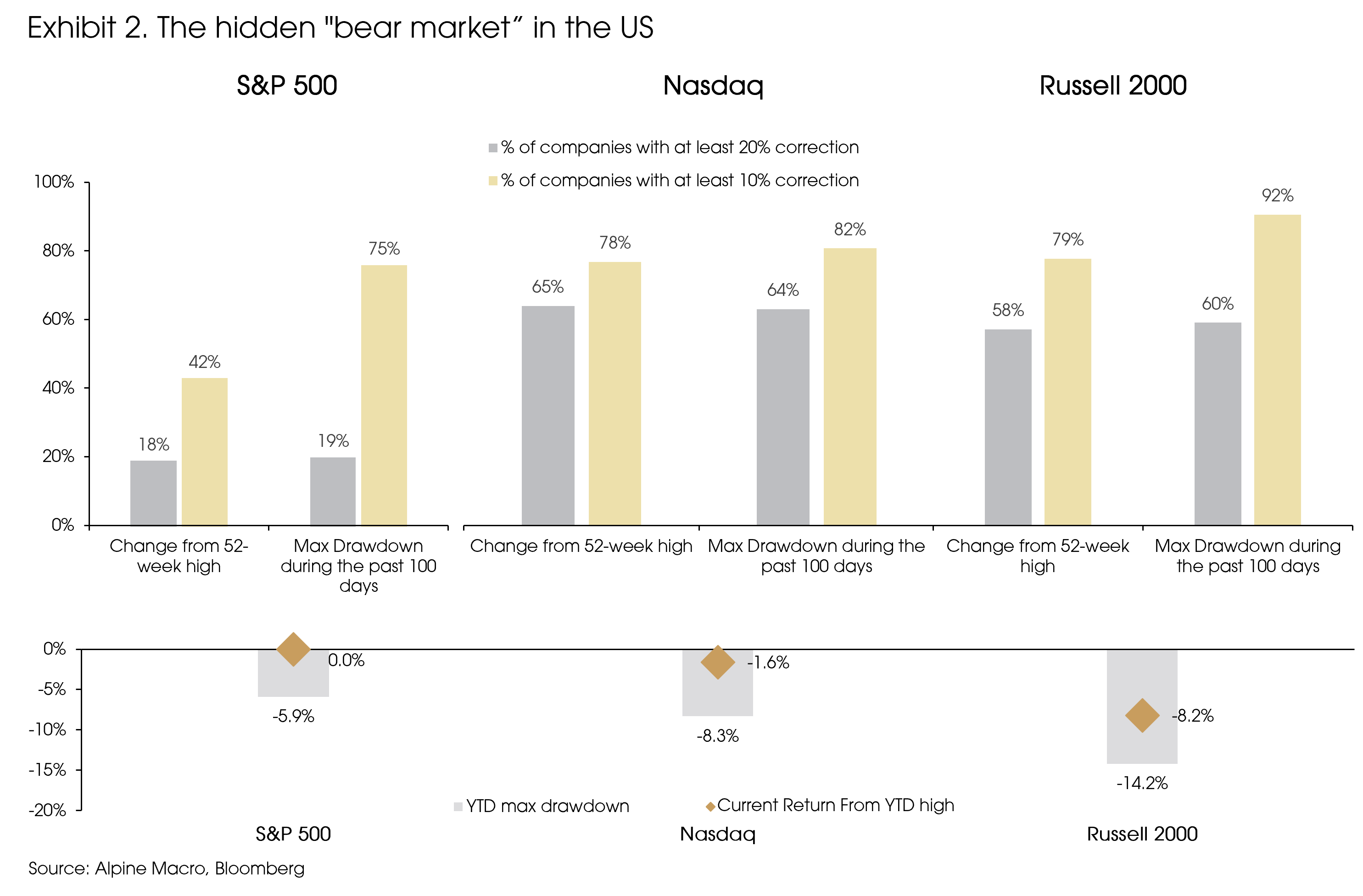

Even for the winning US market, the fading cyclical tailwind in 2H also led to a hidden bear market in some segments underneath the bull run (Exhibit 2). 18% companies in the large-cap universe (S&P 500) have dropped more than 20% in 2021. This number notably increases for the tech universe (Nasdaq) and small-cap (Russel 2000). Most of the corrections came in 2H 2021, suggesting that, apart from the large quality-growth names, the fading liquidity expansion has already led to multiple compression and downturns on the vulnerable segment of the market (e.g., small-cap and non-profitable companies).

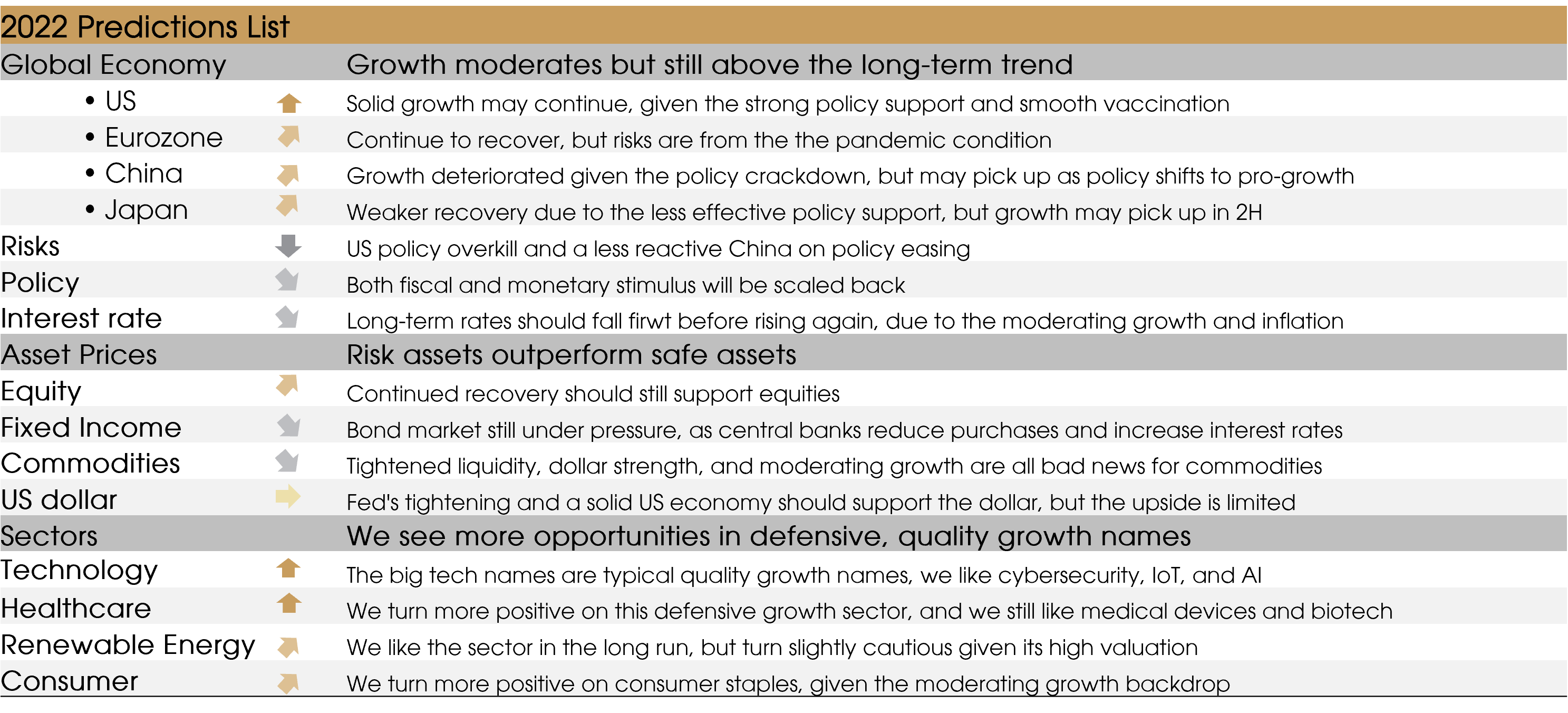

Looking forward, in 2022, growth, policy, and inflation are the most important factors to watch. Global growth should moderate further towards its long-term average. The reduced policy support and the easing supply-side bottlenecks should cap further surges in inflation, and monetary policy may pivot from an aggressive tightening stance if inflation pressure retreats.

Therefore, we stay pro-risk given the continued global recovery. However, we turn more defensive in 2022 and expect the fading cyclical tailwind to extend into 1H 2022, due to the moderated growth and the withdrawal of the expansionary policies.

1. Economic growth will decelerate towards the long-term trend

It has been almost two years since the pandemic outbreak, and it is still far from over. However, we have become more optimistic now than a year ago that the pandemic will become less impactful on economic growth.

We will likely continue to have regional waves and re-imposed restrictions, but the acceleration in vaccines, the booster jabs, and the potential rollout of COVID antiviral medications should all limit the overall impact. Therefore, even with the uncertainty of Omicron and other possible new variants, we do not expect another complete shutdown globally, and economic activities should further normalize.

Further re-opening of economies and the continued normalization of economic and social activities will provide another up leg in global growth, which is expected to remain above the long-term trend in 2022.

That said, global growth will decelerate from the strong level in 2021 as the world normalizes and policy support is gradually removed. According to the IMF, world GDP growth is expected to decline from 5.9% in 2021 to 4.9% in 2022 and return to the 3-4% long-term trend afterwards.

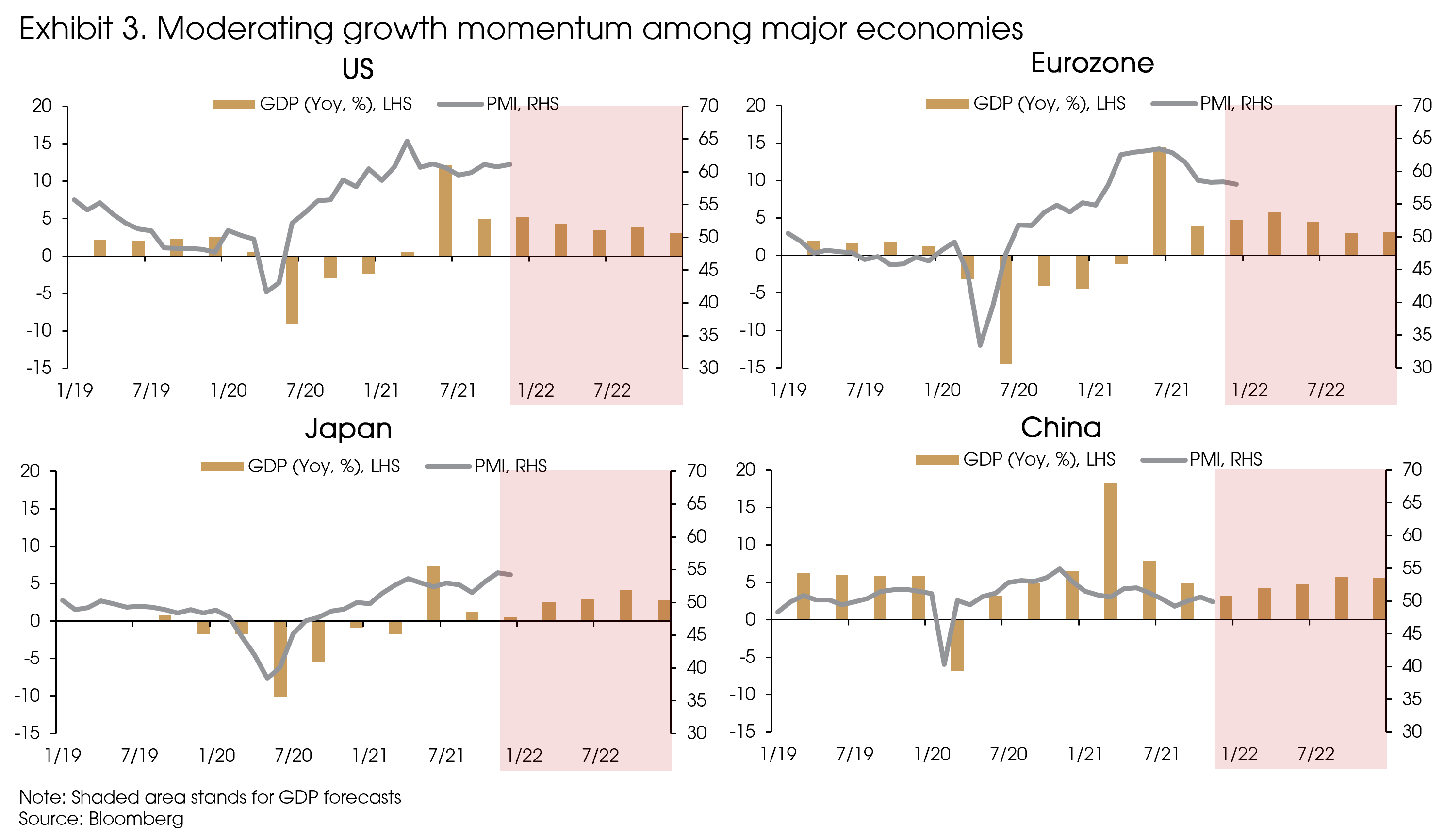

Seen from the recent PMI data, the US showed strong growth momentum among major economies, followed by the Eurozone (Exhibit 3). The large scale of expansionary policies and the smooth vaccination rollout well supported the GDP to return to their pre-pandemic levels.

China’s better pandemic control has helped the economy to first return to its pre-pandemic trend. However, the credit tightening and regulatory crackdown led to a significant slowdown. Japan’s recovery lagged other major economies, with its GDP still below the pre-pandemic level. The aging issue and a higher household savings rate may have resulted in less effective fiscal stimulus.

Looking forward, we expect the current growth landscape to continue in 1H 2022, with the US taking the lead. However, growth in China and Japan may pick up in 2H. The Chinese policy stance has turned pro-growth, while Japan’s weak recovery so far and the promised fiscal support from the new government could drive up economic performance in 2H.

2. Expansionary monetary and fiscal impulses have both reached inflection points

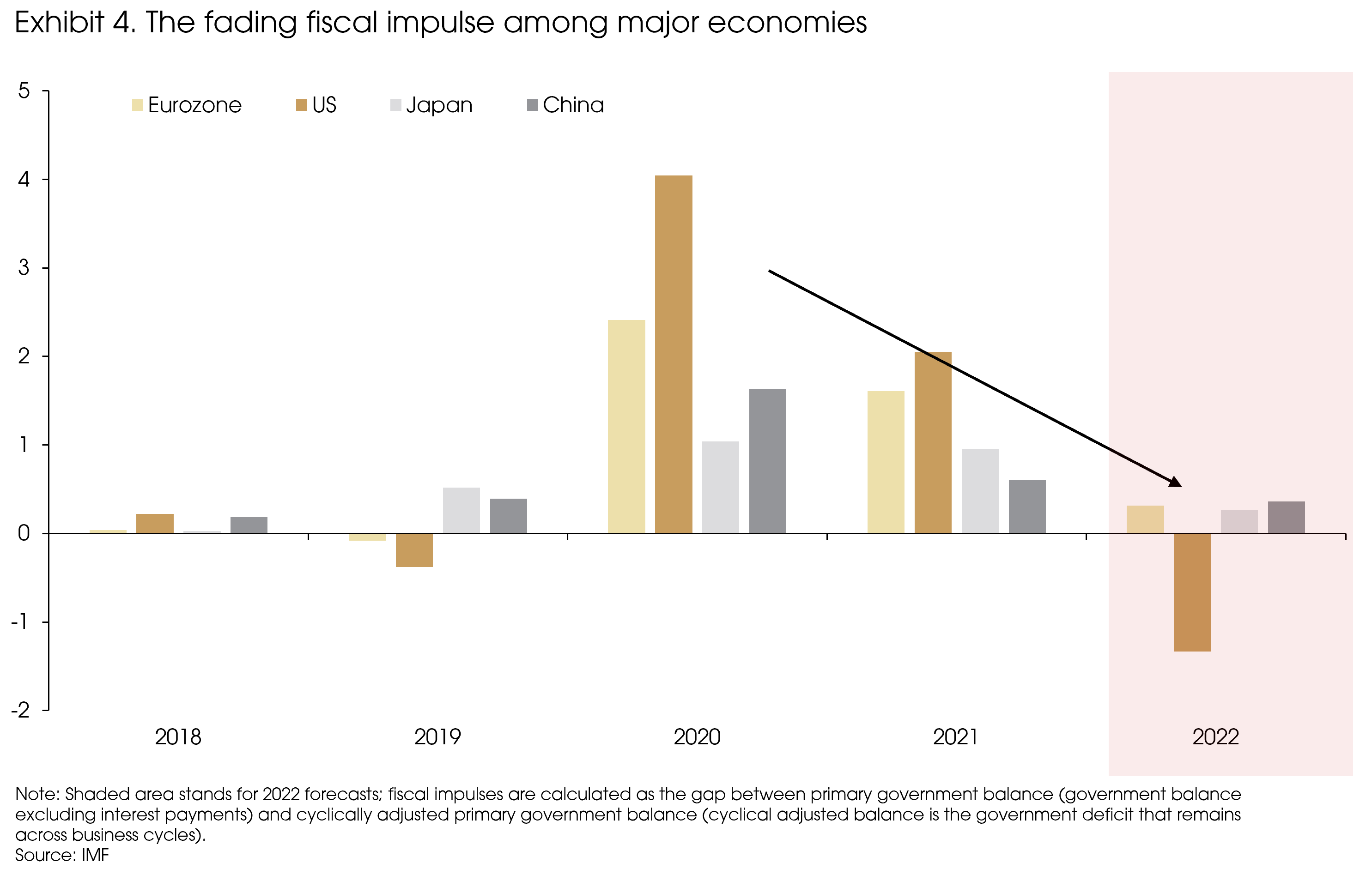

The unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus has well supported the V-shaped recovery in 2021. However, alongside the recovery, the record high government deficits/debt, surging central bank balance sheet, and multi-decade high inflationary pressure in several economies suggest that such policies are not sustainable. 2022 will see significant policy adjustments among governments and central banks.

According to the IMF, government primary balance (government income minus expenditure, excluding interest payments) widened from -1.9% in 2019 to -9.5% in 2020 and -7.8% in 2021 in advanced economies. Fiscal thrusts among emerging market economies are more limited, given their relatively fragile balance sheets. However, the primary balance still widened from -2.9% in 2019 to -7.8% in 2020 and -4.8% in 2021.

With the global economy stepping out of the recession, governments will also move away from the ultra-expansionary fiscal stance. Moreover, as the pandemic condition continues to improve, the emergency spending from governments will significantly decrease. Therefore, the fiscal impulses, which is the net government spending related to specific economic cycles, will notably decline or even turn negative (e.g., in the US) among major economies (Exhibit 4).

On the monetary policy side, the balance sheets of the Fed and the ECB almost doubled compared with their pre-pandemic levels due to the aggressive asset purchases. However, both central banks have announced or have started to reduce asset purchases recently. Liquidity expansion in the market will decrease going forward.

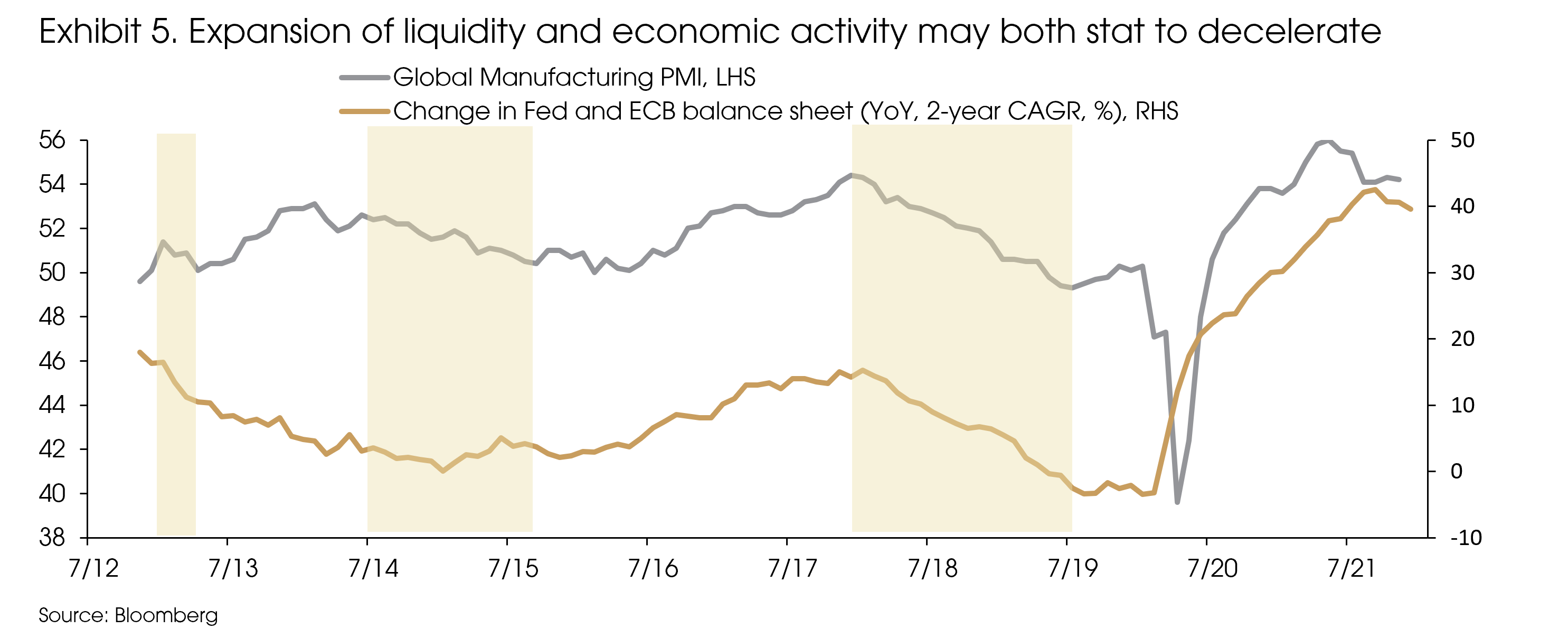

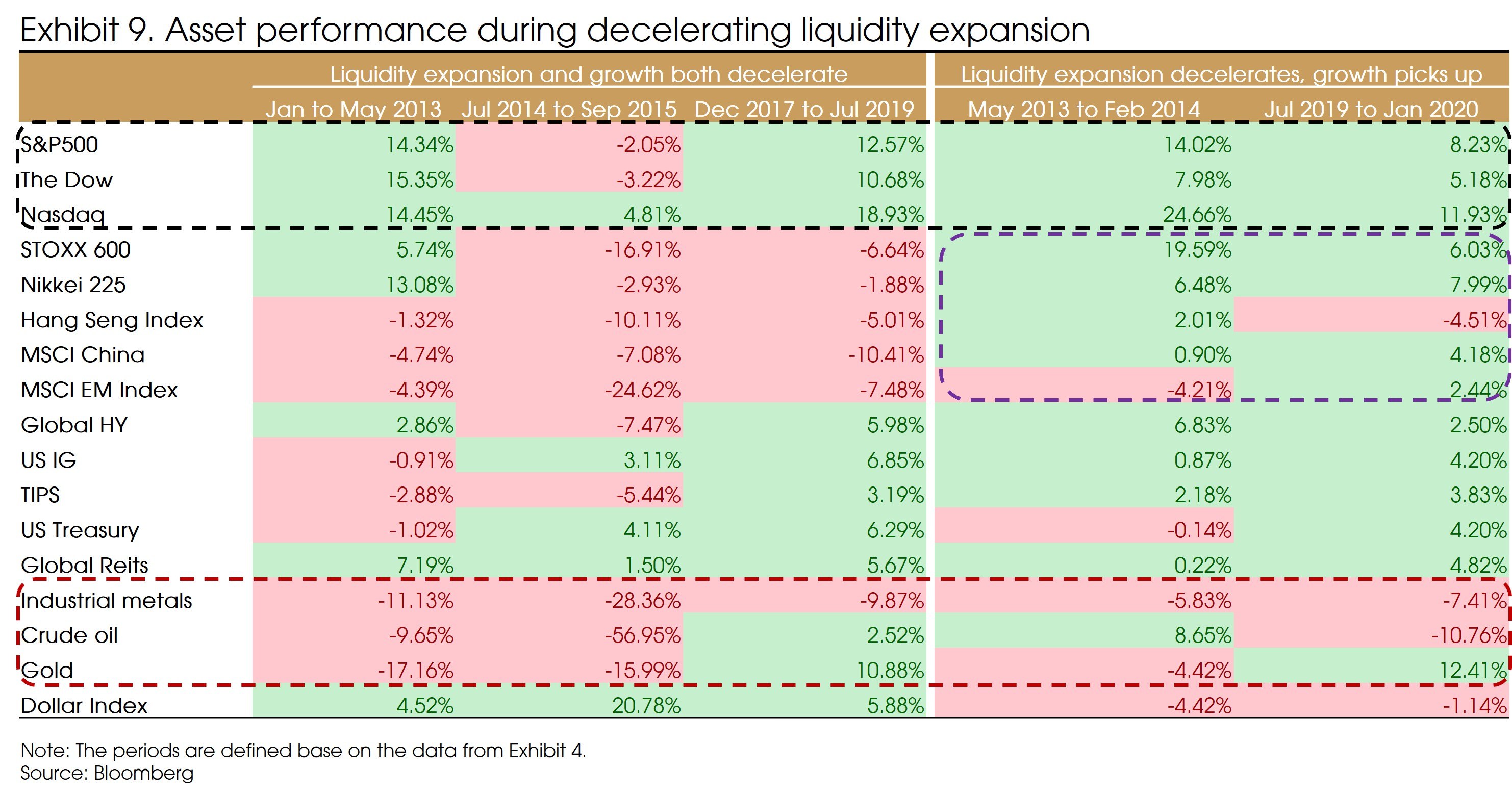

Therefore, both economic growth and liquidity expansion will decelerate in 2022. Similar previous periods were seen in January to May 2013, July 2014 to September 2015, and December 2017 to July 2019 (Exhibit 5). We will examine asset performances during such periods in section 4.

3. Inflation should be transitory, yield curve may continue to flatten

A big surprise in 2021 has been the higher and more persistent inflationary pressure, which led to the increasingly hawkish tone from the Fed with three rate hikes predicted in 2022 (the market has only expected 1-2 hikes earlier).

However, as we have elaborated in the previous report, we maintain the view of transitory inflation. The currently high inflation is mainly due to the supply-demand mismatch, primarily related to the pandemic. Specifically, the government’s transfer successfully supported household income, which led to a surge in consumption. Meanwhile, the persistent supply-side bottlenecks (such as temporary factory shutdowns, the reduced labor supply, and the shipping congestion) led to the supply shortages in various sectors.

That said, supply shocks themselves can hardly lead to consistently higher inflation. Japan and China’s muted inflation can be the exact cases.

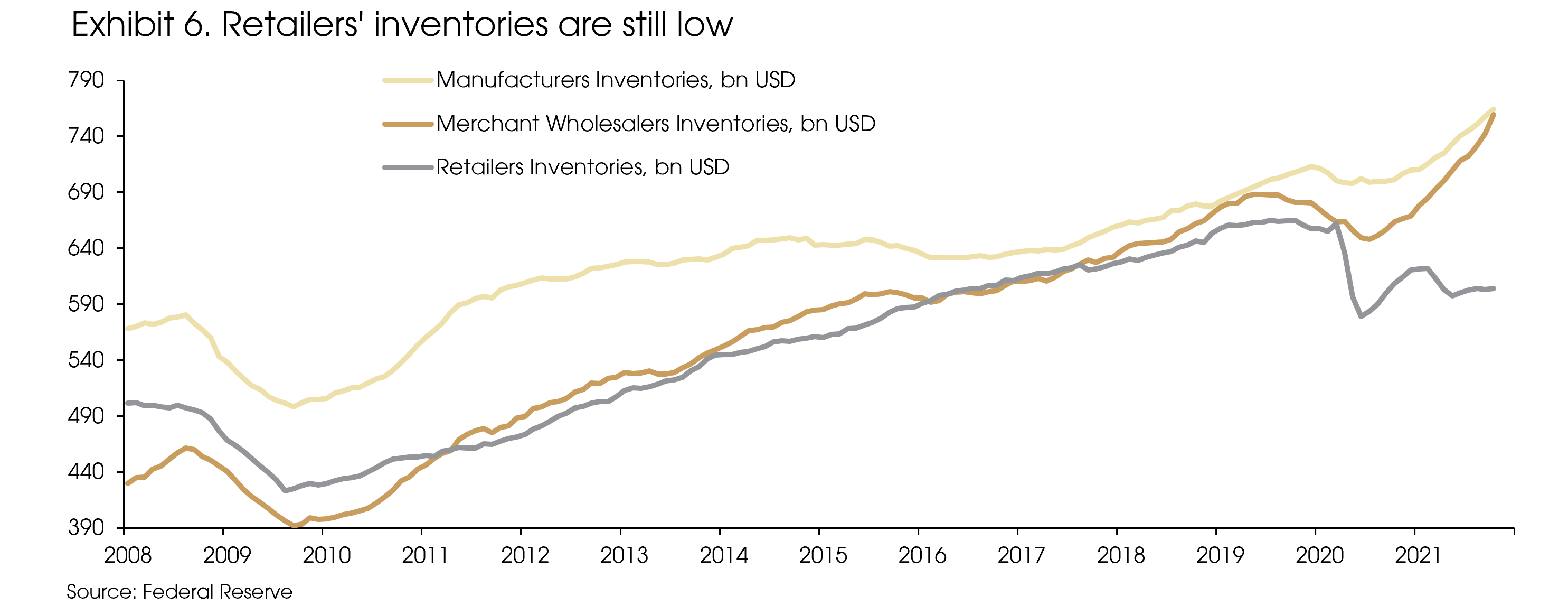

Moreover, supply disruptions will gradually ease. For now, at least a meaningful part of the supply shortage is related to shipping congestion. For example, in the US, both the wholesale and producers’ inventories have reached above the pre-pandemic levels, while retailers’ inventory is still far below the level, indicating disruptions from the shipping process (Exhibit 6). However, shipping congestion is easier to solve than production disruption or the lack of capacity. Therefore, we expect to see a quick improvement from the supply side in early 2022.

Besides, there is also a high bar to have a consistently higher inflation from the demand side. Historically, we only see two factors that can push up inflation in the long run: 1) growing population, which will continuously drive-up consumption, 2) industrial revolution, which can increase capital expenditure in the long run. We do not expect to see either of them in the foreseeable future.

Monetary easing has never been able to do that (the opposite works, though). Fiscal thrusts (by increasing aggregate demand) are more efficient in restoring inflationary pressure. However, the pandemic-relief plans are mostly one-time income transfers, which will fade quickly as the stimulus expires.

Long-term fiscal expansions, such as the US’s infrastructure plan and the Build Back Better (BBB) Act (especially the items related to the green energy expenditure) would be much more impactful in creating excess demand and higher inflation. However, given the reduced size of the infrastructure bill and the major setback of the BBB Act in the Senate, our “transitory inflation” view is further strengthened.

Overall, inflation pressure may stay elevated for the near term but will fall back as demand moderates with fading fiscal supports and the supply chain further normalizes.

The potentially falling inflation mainly has two implications: 1) the Fed may pivot from the current hawkish tone and deliver less than three hikes in 2022; 2) interest rates may fall due to the declining inflation expectations.

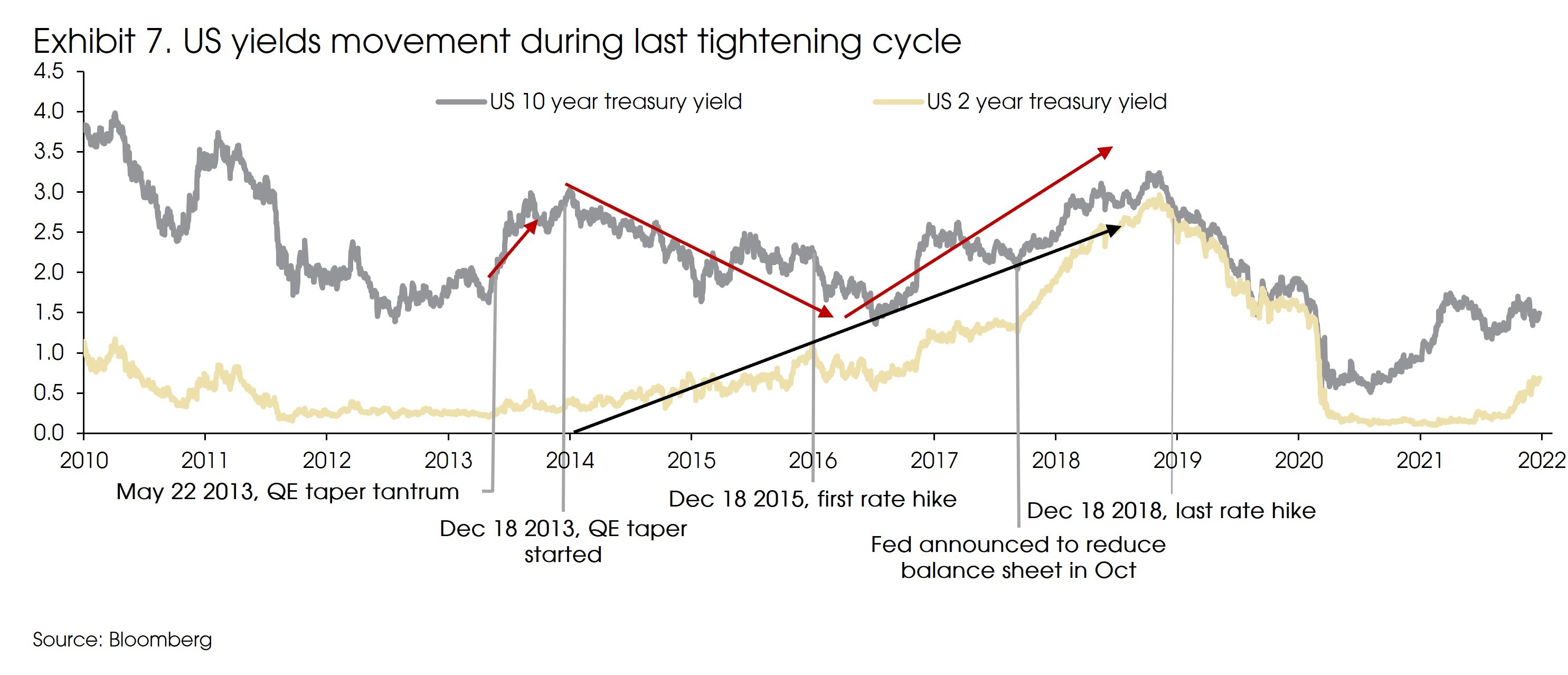

Specifically, seen from the last monetary tightening cycle from 2013 to 2018, the 10-year yield fell after the start of the QE tapering in December 2013, and only rose significantly as Trump’s fiscal stimulus plan led to the reflation trade in late 2016 (Exhibit 7). Overall, monetary tightening (or rate hike) may not necessarily lead to significant increases in long-term yields but rather a flattening yield curve.

Therefore, we expect the 10-year US yield to fall given the weakened growth and inflation outlook, even as the Fed starts to hike the rate soon.

4. Still pro-risk, but turn more defensive at least for 1H

Given the macro backdrop, there are two questions for investors to consider in 2022. 1) Will the Fed’s rate hike lead to a market downturn? 2) What does the combination of tightening policy and weakening growth mean for asset performances?

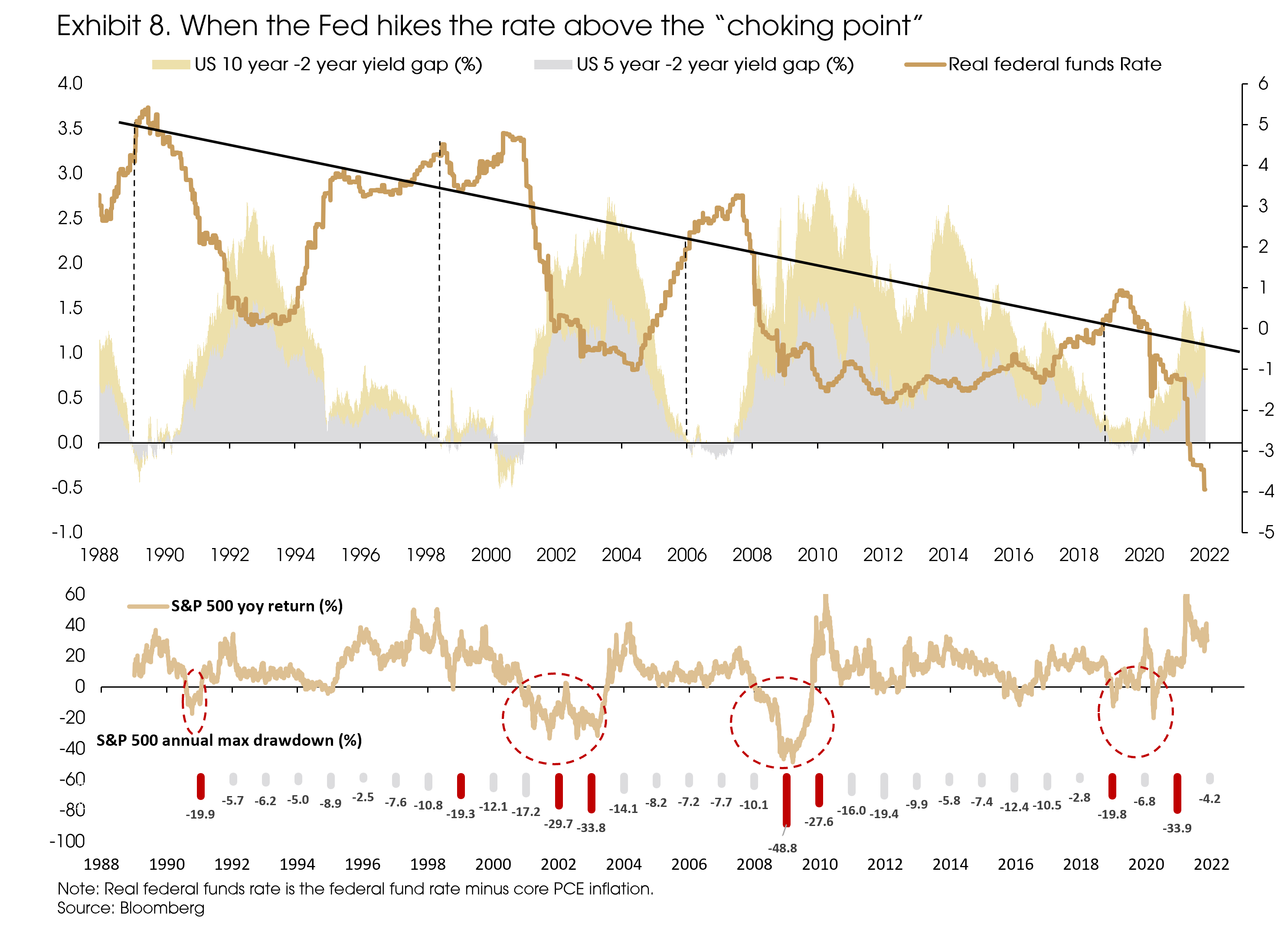

For the first question, historically, stock prices always run into troubles during tightening cycles, but only when monetary policy becomes too restrictive for the underlying economy.

Specifically, since the 1990s, the US market only fell significantly (i.e., negative yoy S&P 500 returns and market drawdown exceeding -20%) when the real federal funds rate reached above the black line in Exhibit 8, or the “choking point” line.

However, we do not expect this to happen in 2022. Exhibit 8 suggests that the current “choking point” for interest rate is around -0.5% to -1%. Meanwhile, the current real federal fund rate is at -4.45%. Therefore, even with three rate hikes in 2022, we are still far away from the choking point or a notable market downturn.

That said, the risk is from inflation. The current core PCE inflation is around 4.7%. However, if the high inflation is transitory and returns to 2%, the real federal fund rate will be very close to the choking point after three hikes. However, for the case of falling inflation, we expect the Fed to turn dovish and deliver fewer rate hikes, as mentioned in section 3. Therefore, in either case, we do not expect to see a market downturn, and we stay pro-risk in 2022.

Historically, the US equities and the dollar were the clear winners during such periods. Moreover, within the equity space, the growth part (e.g., the Nasdaq) consistently outperformed. Meanwhile, emerging market assets and commodities were hit the most by the tightened liquidity and the stronger dollar. Thus, for 1H 2022, bubbly or not, we expect the US market to remain strong.

However, changes may happen in the 2H. As mentioned in section 1, growth momentum from non-US economies may pick up in 2H (e.g., Japan and China). Thus, the dollar strength may start to reverse, which will benefit the non-US markets (Exhibit 9, RHS). Moreover, if the Fed goes further to abandon the hawkish stance, liquidity condition may also improve, leading to potentially more meaningful rallies in emerging market assets (e.g., China) and commodities.

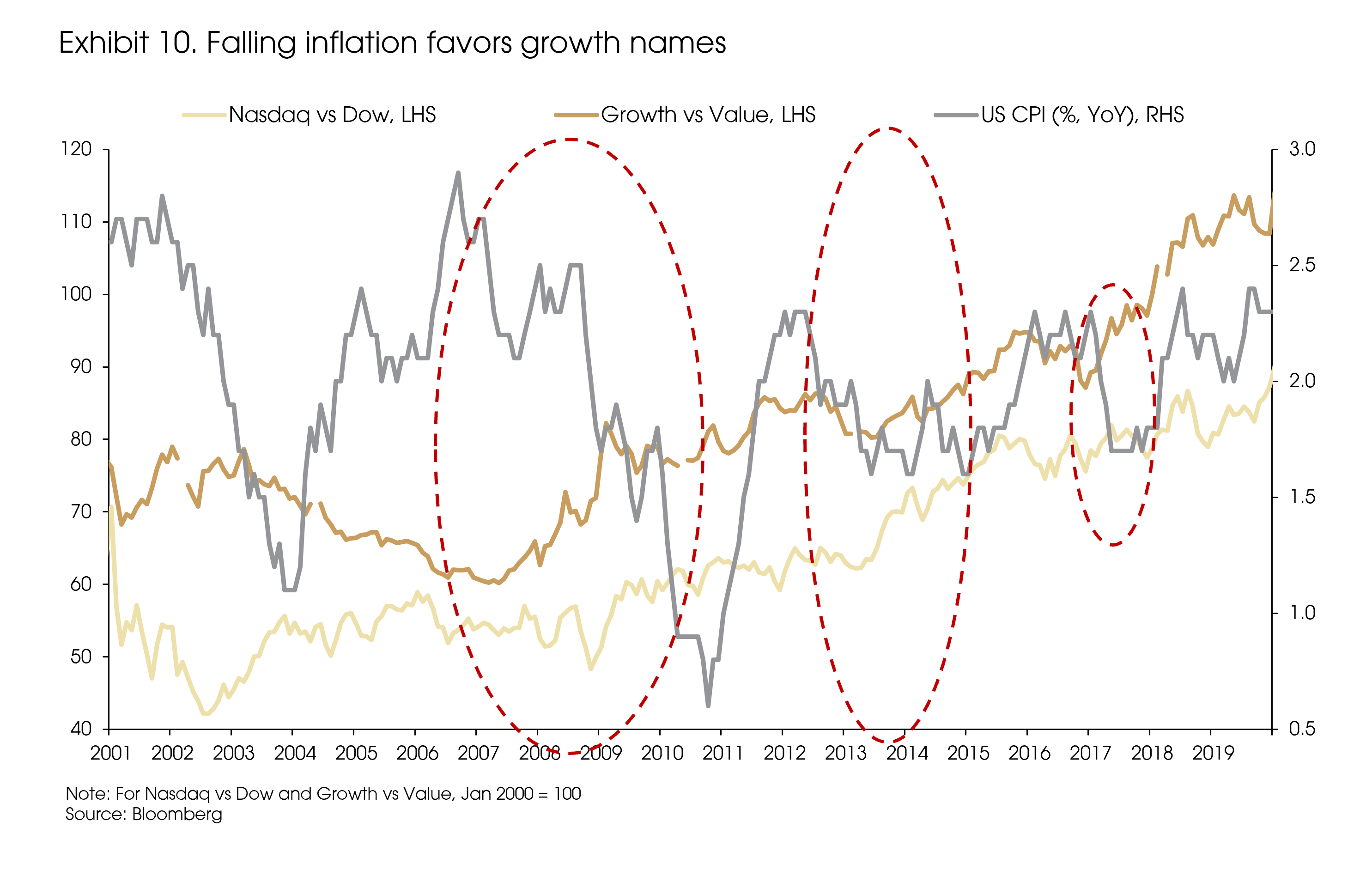

Sector-wise, we expect the cyclical/value play to continue weakening, as the rate of change in monetary and fiscal stimulus has peaked, and the global economy may generate negative surprises. Besides, falling interest rates and moderating inflation will both benefit growth names (Exhibit 10).

Therefore, turning defensive should make a lot of sense in 1H 2022. We advise sticking with the big growth names in the US market or the old winners in the past decade, such as Tech and Healthcare, and turn away from the markets and sectors that are more subject to economic cycles. However, market leadership may rotate towards cyclical again in 2H.

5. Risks: policy overkill from the Fed, and the increased uncertainty from China

The biggest risk to such an outlook is a potential policy overkill from the US. The recent fall in longer-term yields and the significantly flattened yield curve already suggested that the market is worrying about an overly aggressive Fed. If the Fed sticks to the hawkish view while the economic outlook further weakens, it may trigger heavy selling in the market.

China can be a wild card in 2022. On the one hand, after the massive correction in 2021, the Chinese new- economy names have attractive valuations and limited downside. Moreover, the Chinese government’s policy stance has also turned pro-growth. Both may support better performance of the Chinese market, which could contradict our view of “sticking with the US in 1H”.

On the other hand, however, the scaring effect from the policy tightening in 2021 may last longer than expected, especially in the property market. The government may also roll out further regulations on the internet sector. Moreover, policy easing may fall below expectations or be insufficient to support the economy (after all, we have only seen one major move, the RRR cut, so far). Finally, even if everything goes excellent domestically, a potential flare up of the US-China tension could ruin them all. Such risks in China will affect our view that the performance of cyclical assets and emerging markets may pick up in 2H.

Sources: Alpine Macro, Bloomberg, Federal Reserve, IMF