CIO 2025 Outlook: Rising volatility in a risk-on environment

Author: Yao Wang and Jess Cheung Editor: Nicolas Sioné

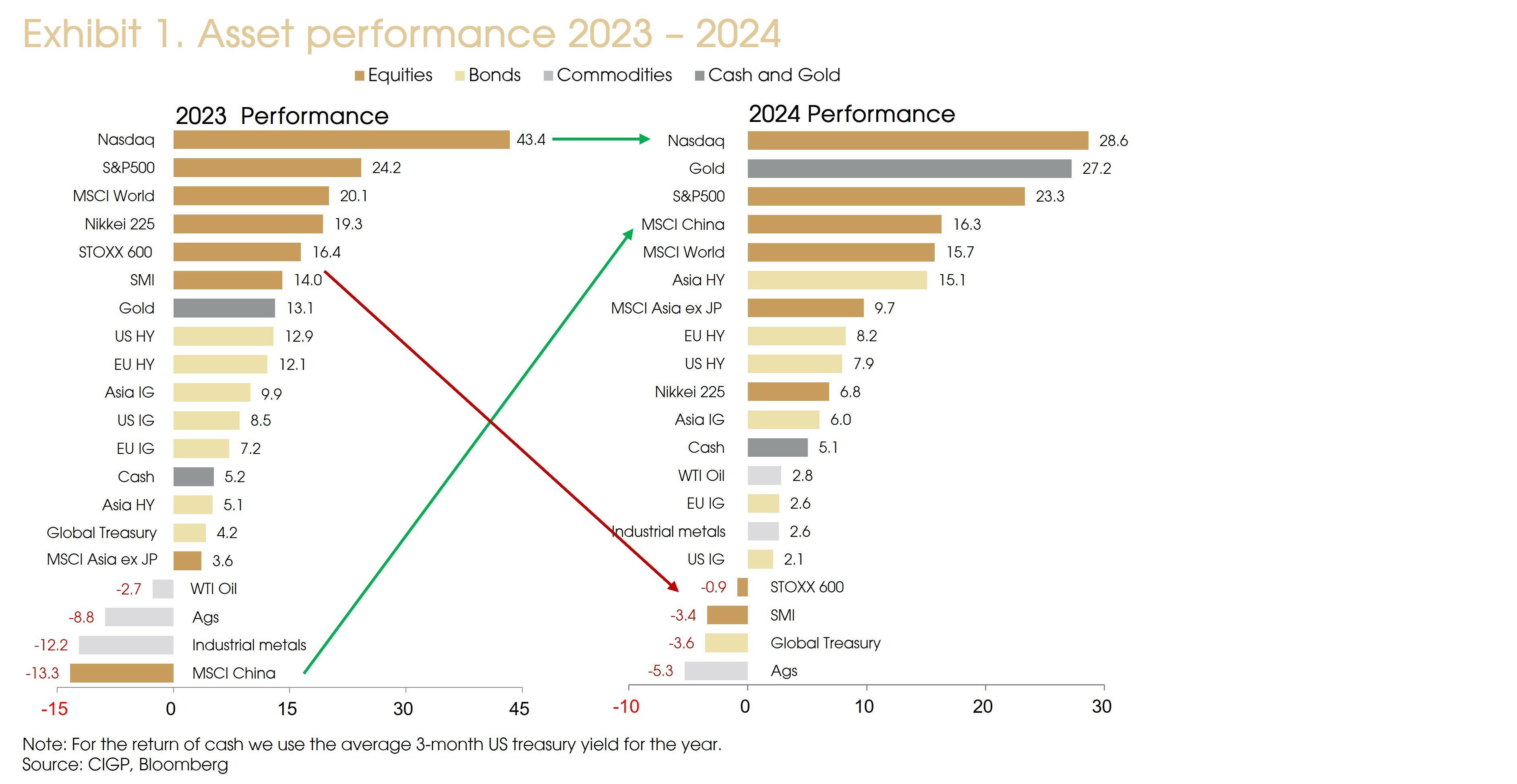

Global Equities enjoyed another good year in 2024. After the 20% gain locked-in in 2023, the MSCI World Index grew by yet another 15.7% last year (Exhibit 1).

The top performer continues to be the US market, and more particularly US tech stocks. In 2024, China rebounded from its 2023 lackluster performance, in the face of weak European market performance. Clear signals from the Chinese government regarding further fiscal stimulus, coupled with weak growth momentum in Europe, may explain this change in performance.

Commodity prices performed better relative to 2023 but remained weak. The return on cash was still significant. Gold had another nice run, driven by ongoing central bank purchases and heightened political uncertainties surrounding a battery of elections last year. The fixed income market also performed well, bolstered by the beginning of monetary easing from major central banks and further narrowing of credit spreads.

1. “US exceptionalism” may persist in 2025

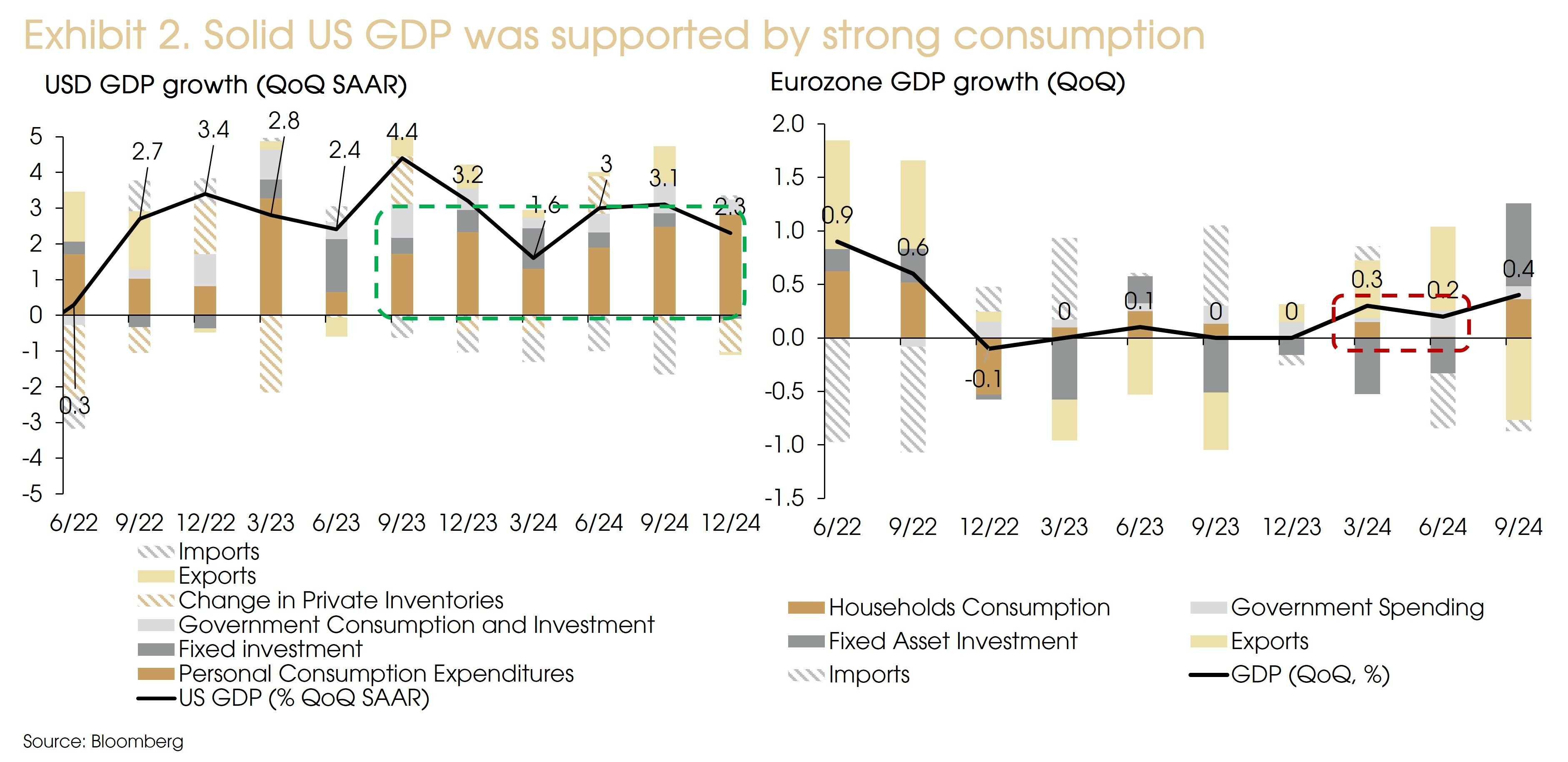

The biggest “surprise” in 2024 was the still very solid state of the US economy. According to preliminary data, the US GDP grew 2.8% in 2024, up from 2.5% in 2023, doubling the market estimate (1.5%) that had been announced as at the beginning of last year. Strong household consumption remains the key driver of such solid US growth (Exhibit 2). Meanwhile, consumption growth in other major economies is far less robust and fails to support a decent GDP growth. For example, the Eurozone’s household consumption has only marginally contributed to GDP growth in 1H 2024.

Looking into 2025, we continue to see positive drivers that may lead to solid and better economic growth in the US versus other versus other countries.

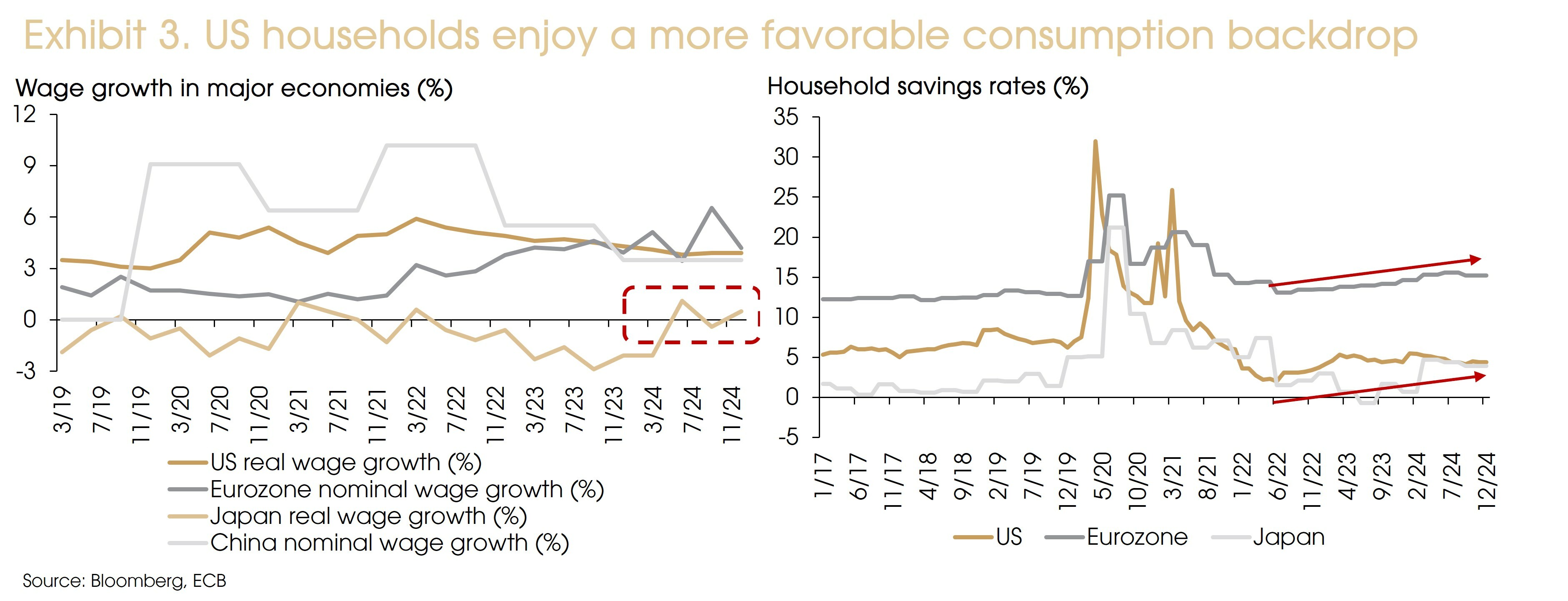

First, the US real wage growth remains stable at higher than the pre-2020 levels, while households’ savings rate declined last year, making for a favorable setting for continued consumption growth (Exhibit 3).

Japan’s real wage growth just turned slightly positive in 2H last year its savings rate followed suit and remained at a higher level versus pre-pandemic period. Meanwhile, the Eurozone wage growth lost momentum in 4Q, while its savings rate increased to its highest level since 2022. The picture is even more negative when looking at China: Lower wage growth since 2022, with high savings rate at well above 30% (double that in the Eurozone). The above continues to suggest better momentum in household consumption from the US in comparison to other major economies.

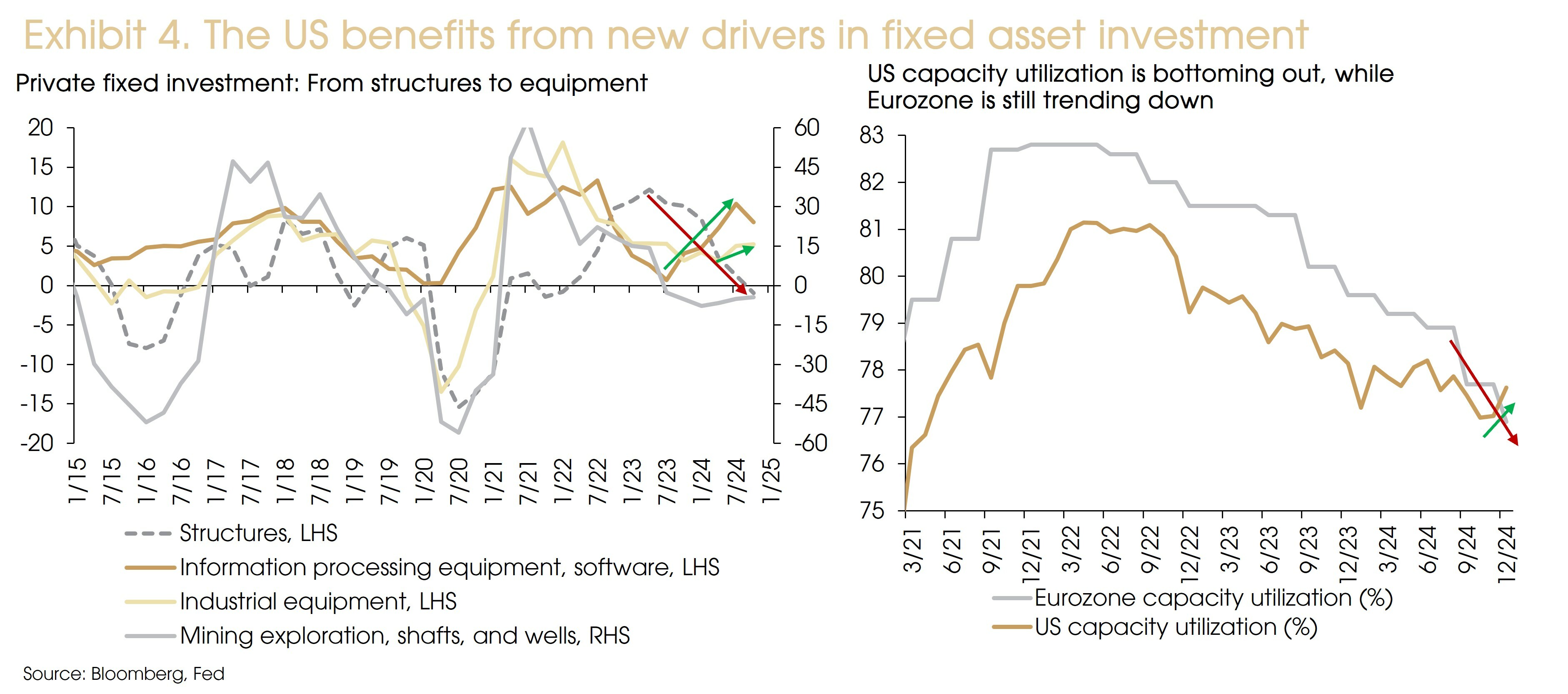

Second, the US also showcases a better outlook in regard to fixed asset investments. The boost in construction spending subsidized by the CHIPS Act and IRA has plateaued in the US, resulting in negative growth in fixed investment from structures last year (Exhibit 4, LHS). However, AI related investment has been s key support for fixed investment growth in the US, and the pick-up in equipment spending is expected to drive growth going forward.

It usually takes 2 years to build manufacturing facilities (semiconductors facilities will take longer), and equipment spending typically takes place 2-3 quarters before the factory construction is completed. This means that a manufacturer who started building a factory in early 2023 (the IRA and CHIPS related credits came into effect in January 2023) will not be purchasing equipment before 2H 2024.

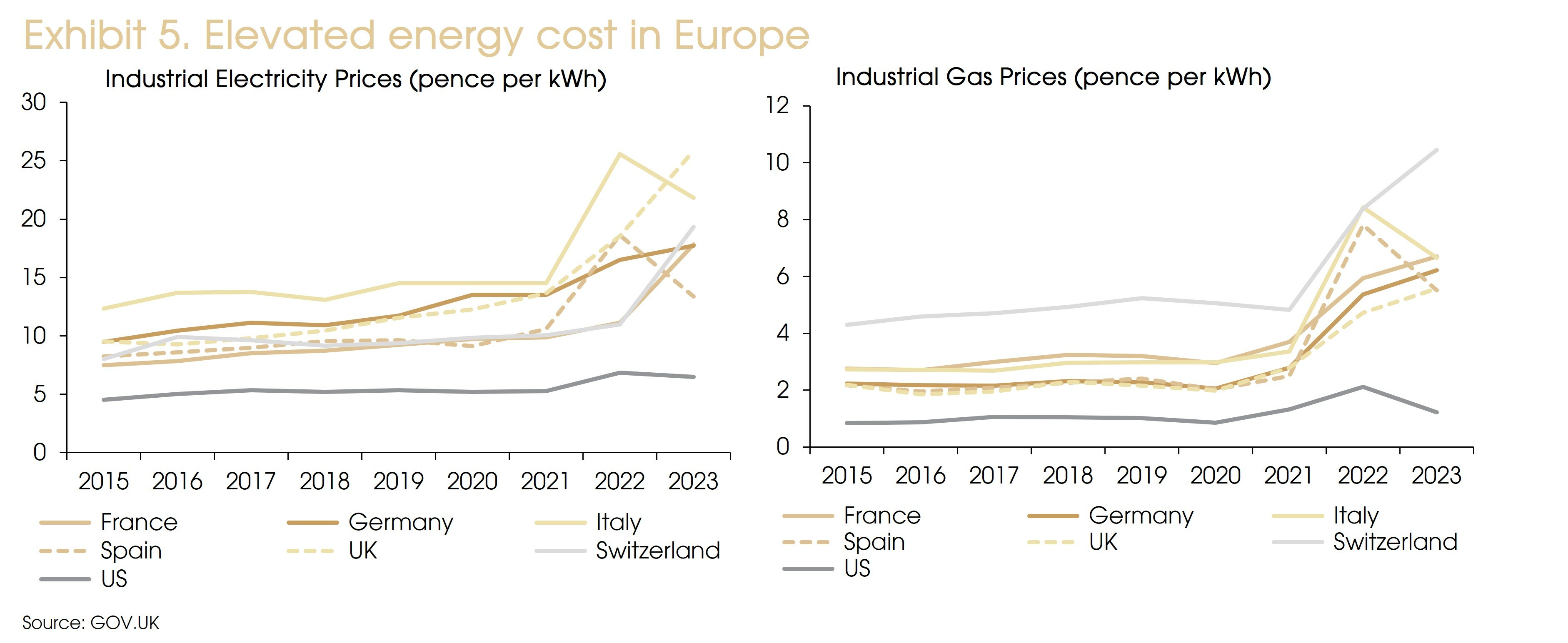

Outside of the US, we did not observe clear drivers of business investment in other major economies. The nearly doubling in energy costs continues to pose a significant hurdle for fixed asset investment in Europe (Exhibit 5). As a result, the Eurozone’s capacity utilization rate (a leading indicator for capex) kept declining since 2022 (Exhibit 4, RHS).

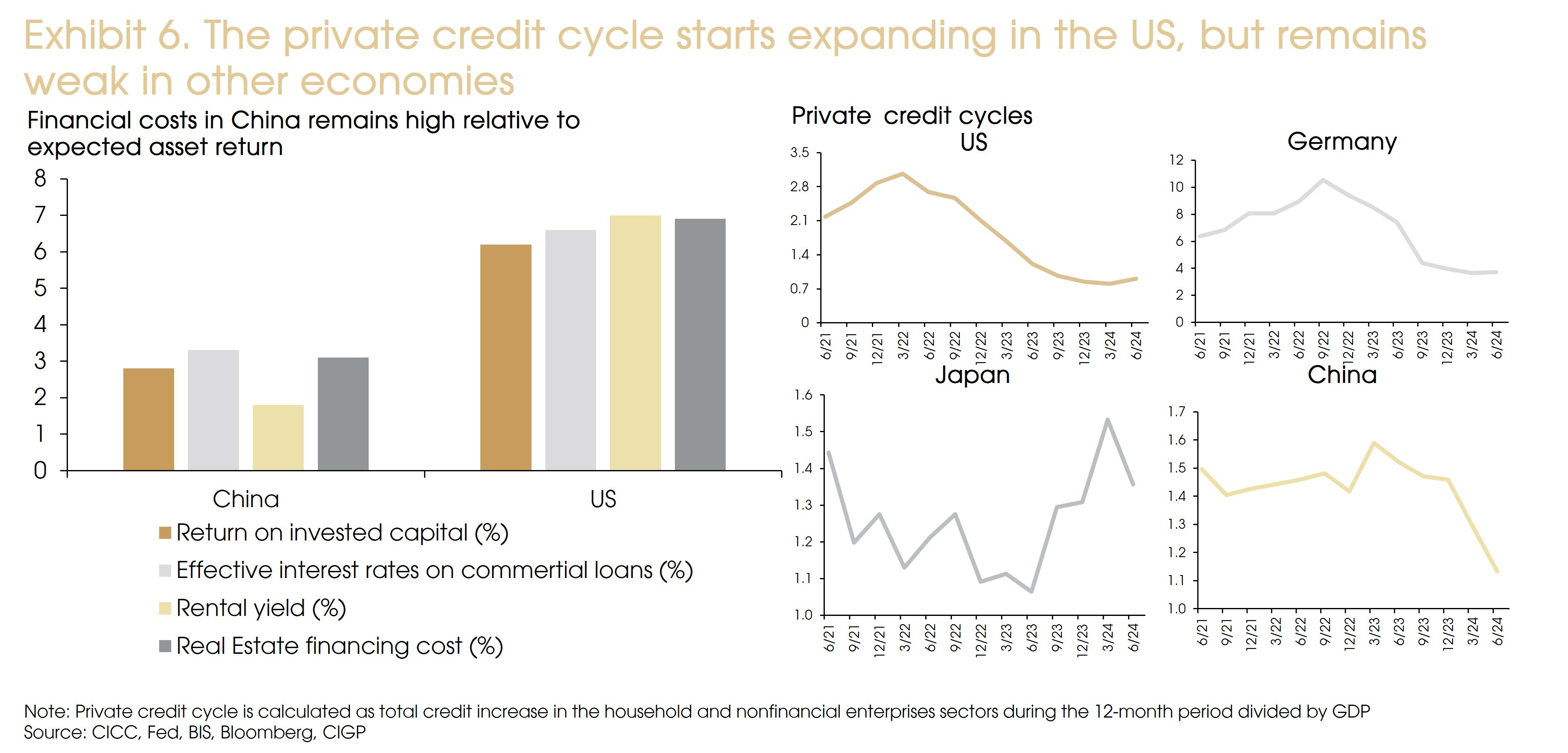

Rate hikes in Japan will raise financing costs. Meanwhile, low returns on asset/investment continue to apply pressure on the already low business and consumer confidence as well as low consumption and investment growth in China (Exhibit 6, LHS).

Therefore, even with a higher interest rate, the US private credit cycle started bottoming out since 2H 2024, while credit growth in other economies remained weak (Exhibit 6, RHS).

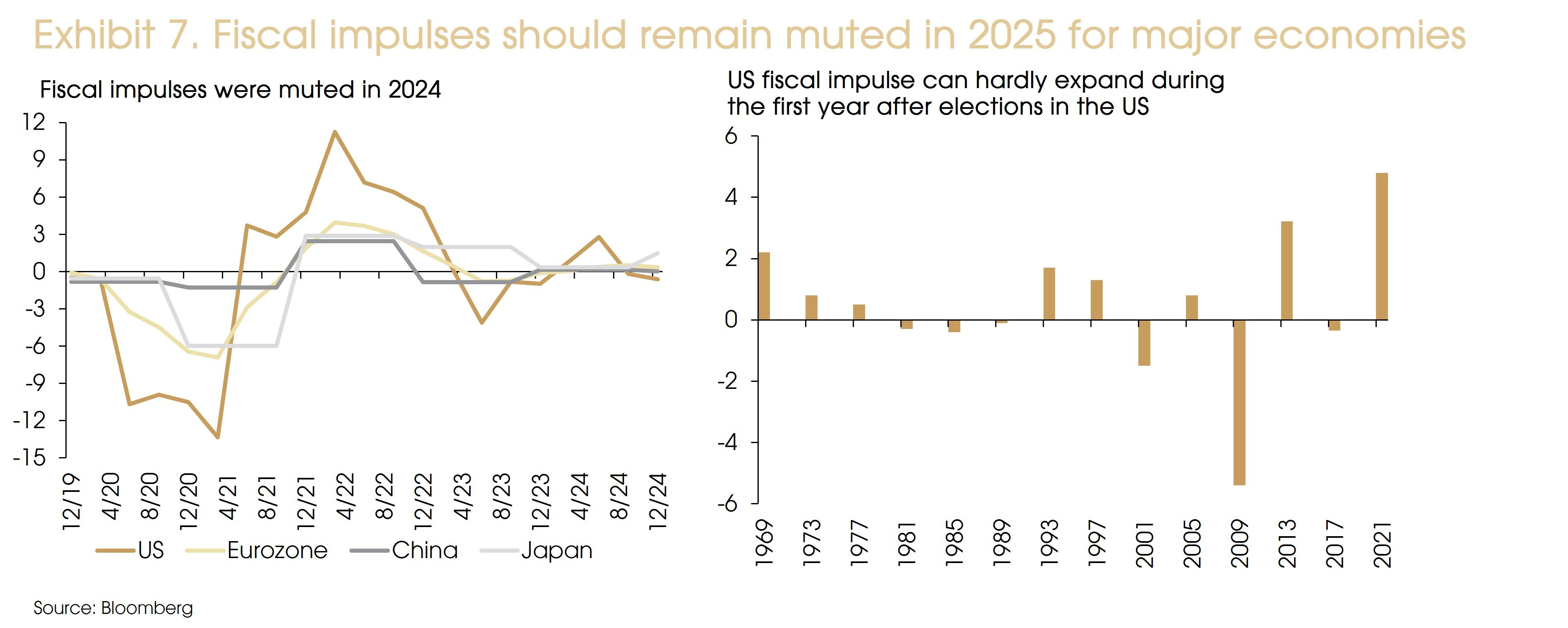

On the fiscal side, we see a more balanced outlook across major economies. In 2024, fiscal spending slightly increased in the US, while it slightly decreased in other economies. However, the observed differences were not meaningful (Exhibit 7, LHS).

It is hard to significantly increase fiscal spending during the first year following elections in the US (Exhibit 7, RHS). Both Europe and Japan are facing political constraints in increasing deficits while China has the potential to implement a larger fiscal stimulus. However, such a larger stimulus will likely result from a significant external shock, such as higher tariff hikes on Chinese goods. For now, we expect a muted fiscal impulse in major economies.

Overall, the US economy has more positive growth drivers and fewer hurdles compared to others. Therefore, we anticipate relatively stronger growth momentum in the US for 2025.

2. Risks: A weaker US economy with higher inflation

However, risks to the outlook are skewed towards a narrower lead of the US economy. Domestically, last year’s significant downward revision on its payroll data last year, as well as the potential link between its healthy household balance sheet and gains from the equity market, both pose further risks to consumption growth in the US.

In addition, both a milder tariff hike (benefitting non-US economies) and a more aggressive tariff hike will likely narrow the gap between US and non-US growth. In an extreme case where the US hikes tariff on every trading partner by 10%, we are unlikely to see significant supply chain relocations among non-U.S. economies (unlike in 2018). US importers, businesses, and consumers will face higher prices on nearly all foreign goods they purchase, hitting the US economy.

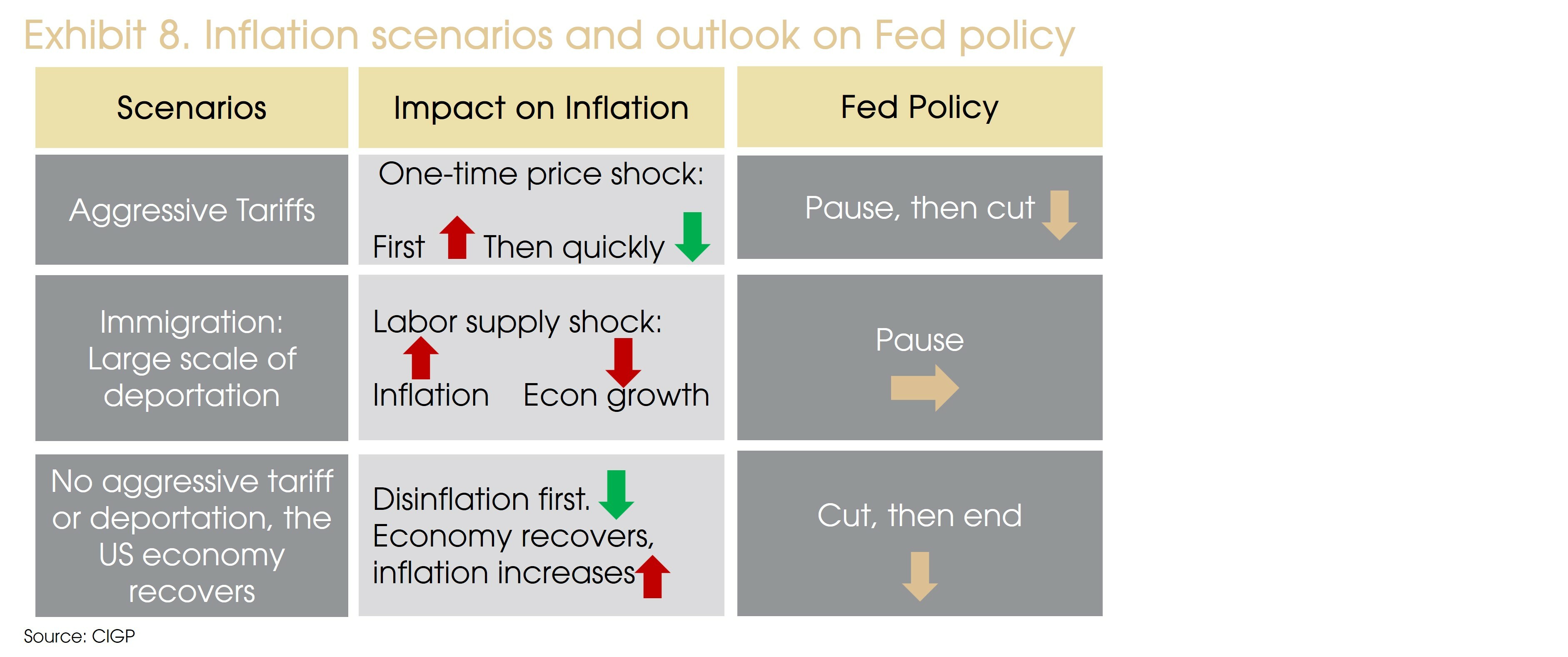

Another concern is inflation risks, which may lead to rate hikes from the Fed. However, overall, we do not expect to see a significant and sustained increase in inflation even after considering some extreme cases on tariffs and immigration (Exhibit 8).

First, sustained inflation pressure arises from excess aggregate demand in an economy. For example, in 2022, the Russia-Ukraine war resulted in a significant supply shortage, while the large scale fiscal stimulus continued to boost demand. This prolonged imbalance within which demand exceeded supply, led to higher inflation.

However, tariffs are one-off price hikes, distinct from a supply shock, as supply remains relatively unchanged, albeit at higher prices. Higher prices typically lead to falling, not rising, demand. Consequently, tariffs should only cause a short-term increase in price levels, followed by weakening economic growth and declining inflation.

In this case, the Fed will probably pause rate cuts due to rising price pressures first, and resume cutting once the economy slows and inflation moderates (similar to 2019).

Another inflation concern stems from Trump’s threat of large-scale deportations, which could result in labor shortages and increased wage growth. However, labor shortage is “stagflationary” as it also results in lower growth. For example, labor shortages will cause delays and declines in business investment and production.

At the current stage, the Fed will likely prioritize growth over inflation and will probably be much more tolerant on rising prices than it was in 2022. Why? The current federal funds rate stands at around 4.5%, which may not be very restrictive but certainly not loose either. In contrast, the policy rate was at 0% at the beginning of 2022, i.e., no brakes on rising prices. While the Fed had to hike rates in 2022, the level justifying for a switch to rate hikes this time around is much higher.

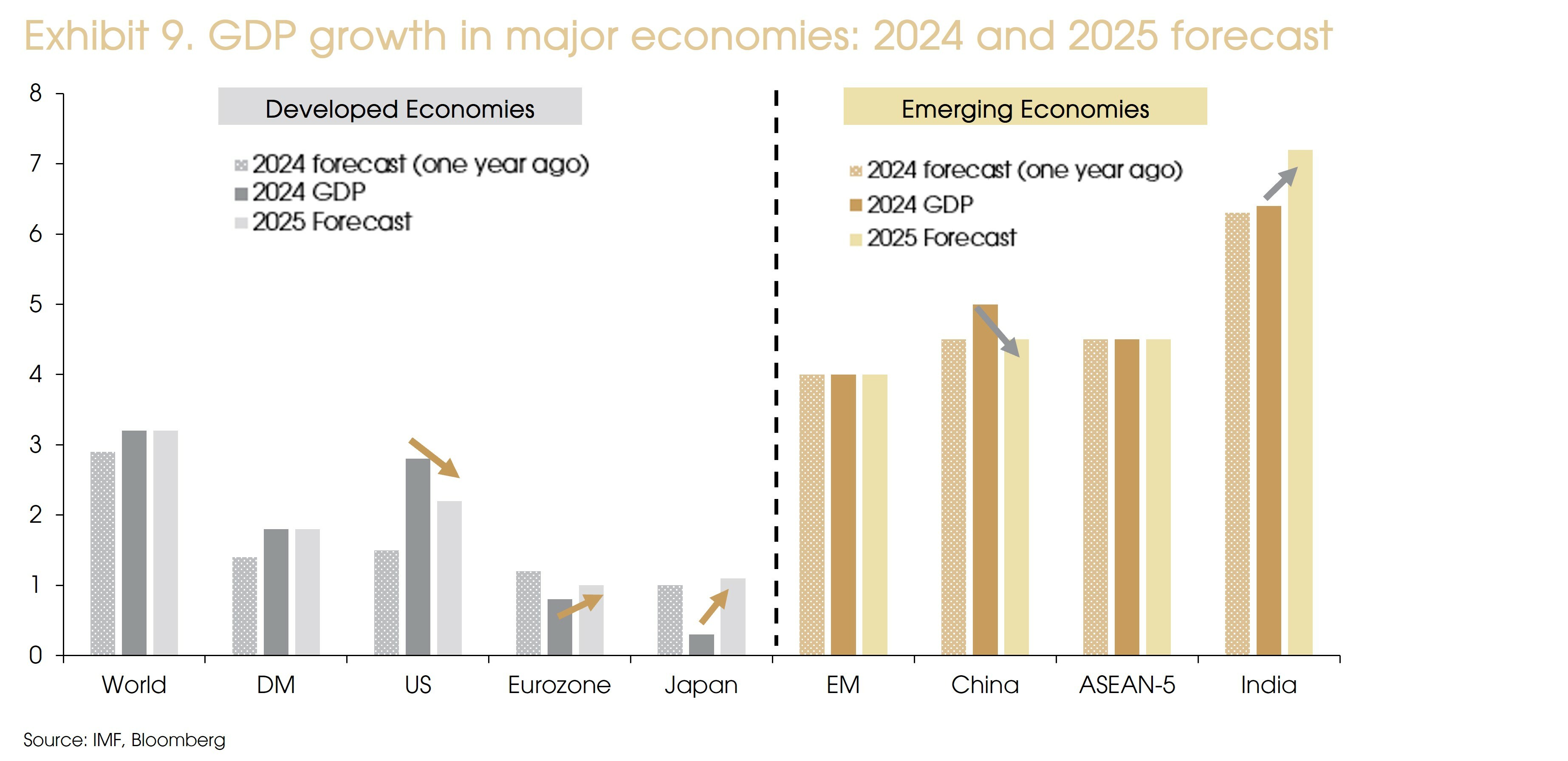

In sum, in our baseline case for 2025, we expect to see a solid US economy, recovering but still weak growth in Europe and Japan, and slightly weaker China growth compared to 2024 (Exhibit 9). Europe and China should therefore continue to ease monetary policies, the Fed is expected to deliver zero to two cuts in 2025 (bottom line: no rate hikes), and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) should continue with its dovish tightening.

3. Equity views: Still risk-on, but increase diversification

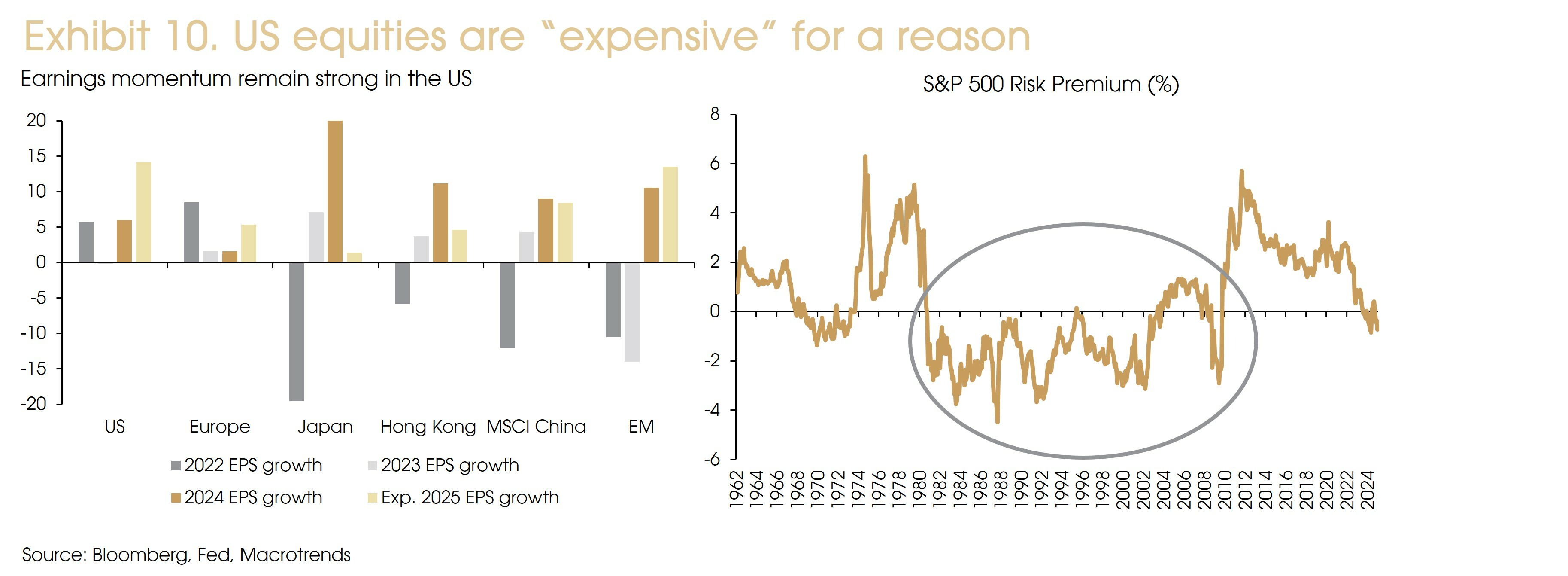

Our baseline case continues to support the risk-on sentiment adopted by the market. We remain positive on US equities, as their solid economic fundamentals suggest better earnings momentum versus other markets (Exhibit 10 LHS). Meanwhile, even with a notable valuation expansion, US equities are not unreasonably expensive: equity risk premium (earnings yield minus 10-year treasury yield) turned negative, but it was the norm in the longer-term before the 2008 financial crisis (Exhibit 10 RHS).

We remain positive on US tech companies, given their decent earnings growth. Particularly, we do not view the emergence of DeepSeek as an added risk towards a possible "AI bubble burst." The solid balance sheets of major US tech companies are a key difference in comparison to the 1999-2000 period.

It could be too early to call the impact on the US AI sector. Nonetheless, we rather see DeepSeek as a potential catalyst for an acceleration in AI development and usage (more competition and lower costs).

This may lead to lower capex spending on AI hardware from some companies in the near-term, should they decide to pause and re-assess their forward capex plans. However, in the long run, it should drive higher levels of spending if the incumbent AI developers want to maintain/extend their lead in AI capability.

In the short-term, there could therefore be some de-rating risks among US AI infrastructure related names, especially the ones that had a super bull run since 2023.

However, such a potential de-rating should not derail the overall positive US market or growth stocks trend. The potentially lower computing costs will benefit large tech companies that already have established AI applications and are opening up to a wider mix of emerging software.

We remain cautious on the European and Japanese markets due to their weak domestic fundamentals. Between the two, however, we are slightly more positive on Europe, as the European market is less correlated with the US tech sector and will benefit more from a potentially larger Chinese fiscal stimulus. Meanwhile, continued rate hikes from the BoJ remain a concern.

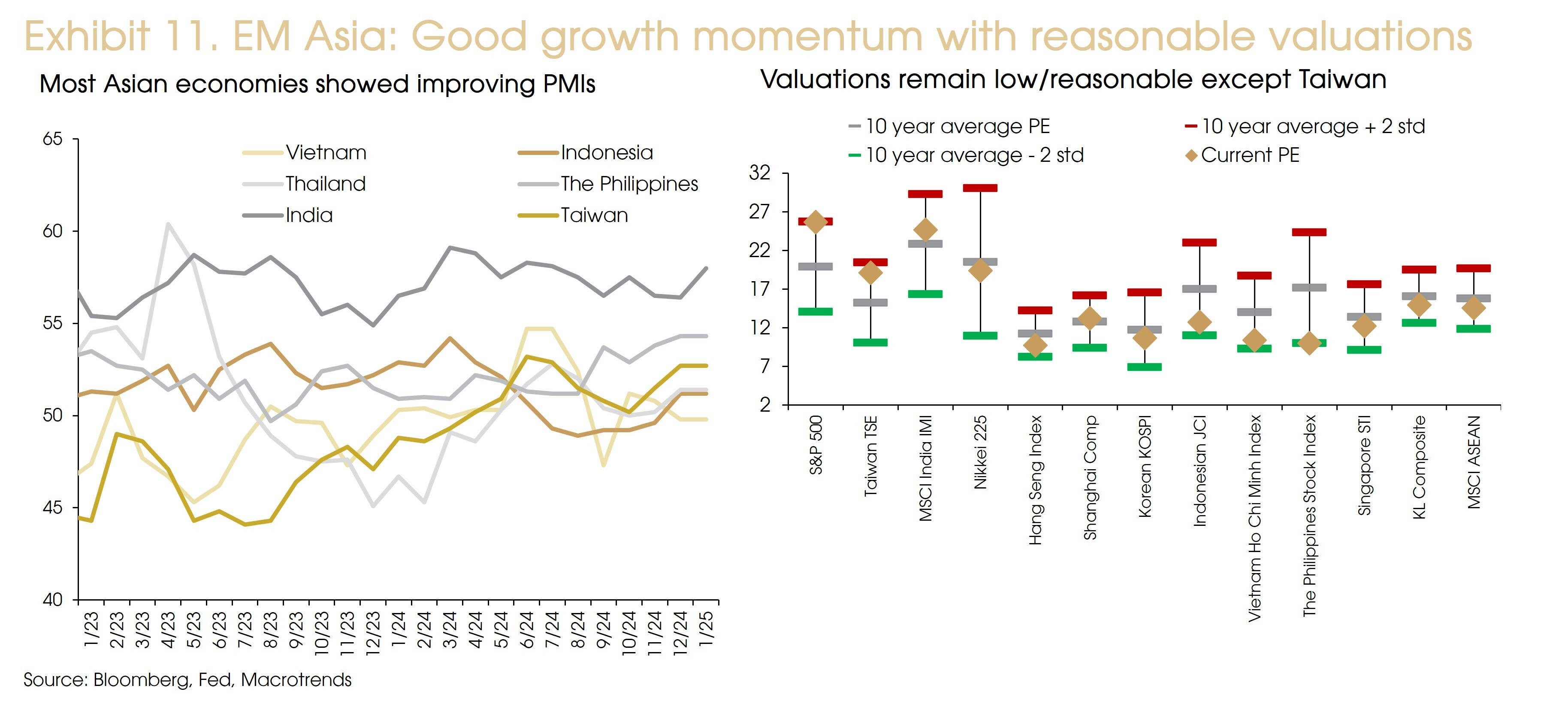

We see good growth momentum among Emerging Asia economies, with still-cheap valuations (Exhibit 11). We thus prefer markets primarily driven by domestic demand, such as India and Indonesia.

We hold a neutral stance on supply chain relocation beneficiaries (e.g., Vietnam, Malaysia). We are cautious about US tech supply chain-related markets, like Korea and Taiwan—not because they may experience significant downturns, but because they are too positively correlated with US tech names, thereby offering little diversification benefit.

Finally, we see more attractive trends in the Chinese market: 1) The tariff actions so far resulted in a broader negative impact on global equities, including the US’s, but a milder hit on China when compared to 2018, signaling that China is better prepared for tariffs than most other markets, including the US. 2) The emergence of DeepSeek may not necessarily lead to a de-rating in US tech names, but may restore some confidence in Chinese tech names, paving the way for a potential re-rating.

4. Fixed income views: Europe looks interesting

US: Attractive bond yields while being nimble on duration trades

The US yield curve, which had inverted for two years, has now returned to a normal upward trending slope, with long-term yields now exceeding short-term yields. Trump’s policies have pushed yields significantly higher in 2024. This has made bond valuations more attractive.

We are still in a rate cut cycle even though at a much slower pace than anticipated. Compared to the historical cycle, the current cycle is still largely underperforming. In the meantime, any decline in the front-end yield will eventually impact longer-term bonds due to the high sensitivity.

Should we see no rate cut in 2025, these may resume in 2026 should Trump ultimately implement extreme tariffs globally. However, given the already elevated long-term Treasury yields, there is limited upside for longer-term yields to rise further.

However, adding duration on dips and reducing it when yields decline makes more sense. Investors should avoid being overly aggressive in locking in duration since there are still headwinds, such as uncertainty surrounding trade policy actions, that could lead to elevated inflation levels.

US IG credit spreads remain tight and are currently trading 15% percentile in 30 years, this is likely to extend to 2025 given the strong demand. Given that the spread tightening should be limited, bond returns in 2025 will primarily come from a decline in treasury yields rather than further spread compression. Meanwhile, the low default rate and strong demand are expected to continue supporting tight spread levels.

Similar to IG, we anticipate limited spread compression in the HY space while current market demand and low bond supply continues to support tight spreads. Default rates are expected to remain modest, with most risks concentrated among weaker issuers. Furthermore, the maturity wall for high-yield issuers remains favorable. The risk-reward profile for BB-rated credits in HY space are more attractive. In the leveraged loan market, default risks and refinancing risk in 2025 are higher compared to the HY space.

Europe: Economic growth and rate cuts are to support the bond market ... but beware of domestic political uncertainties.

In Europe, ongoing disinflation, combined with sequential ECB rate cuts, should provide additional support for the bond market. However, weakening economies will create some downside risk, which could potentially lead to a moderate spread widening.

Indeed, credit spreads for Euro IG and HY bonds are currently 30–50 bps cheaper than their USD counterparts. Spreads are trading in the 32% percentile of the past 25 years. Although still expensive, we think it still offers a more attractive relative value versus the USD bond market alternative.

We therefore anticipate that the decline in German Bund yields, driven by the impact of ECB rate cuts, will likely offset the impact of widening spreads, and continue generating positive returns in 2025.

On the other hand, Germany is currently undergoing a series of political events. The German election on 23 February 2025 will be critical for markets, especially regarding the fiscal outlook.

The potential removal or relaxation of the debt-brake rule could pave the way for higher fiscal spending, supporting economic growth in Germany. Germany’s healthy debt level suggests that long-term Bund yields are unlikely to rise significantly, even if fiscal expansion is to occur.

We maintain a positive outlook on Euro IG bonds, which are expected to remain resilient in the near term. The European bond market remains attractive, with Euro IG bonds offering compelling value relative to USD bonds. Despite the potential for credit spreads to widen slightly due to economic weakness, strong fundamentals and ECB rate cuts should provide a supportive backdrop for European bonds.

5. Commodities remain an investment theme in 2025

Finally, we continue to see commodity exposures as an investment theme in 2025. Inflation remains a sensible concern this year under Trump’s administration. While we believe a temporary increase in inflation is unlikely to trigger rate hikes from the Fed, it could shift market focus toward potential inflation hedges.

Disclaimer

This document is issued by Compagnie d’Investissements et de Gestion Privée Group (“CIGP”), solely for information purposes and for the recipient’s sole use and shall not be further transmitted to third parties. You have been provided with this document in your capacity as Professional Investor(s) as defined in Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571). If you do not meet the Professional Investor criteria, please disregard this document.

CIGP does not assume responsibility for, nor make any representation or warranty (express or implied) with respect to the accuracy or the completeness of the information contained in or omissions from this document. None of CIGP and their affiliates or any of their directors, officers, employees, advisors, or representatives shall have any liability whatsoever (for negligence or misrepresentation or in tort or under contract or otherwise) for any loss howsoever arising from any use of information presented in this document or otherwise arising in connection with this document. This document may not be reproduced either in whole or in part, without the written permission of CIGP. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. There can be no assurance that forecasts will be achieved. Economic or financial forecasts are inherently limited and should not be relied on as indicators of future investment performance.

This document is not a prospectus and the information contained herein should not be construed as an offer or an invitation to enter into any type of financial transaction, nor an act of distribution, a solicitation or an offer to sell or buy any investment product in any jurisdiction in which such distribution, offer or solicitation may not be lawfully made. Certain services and products are subject to legal restrictions and cannot be offered worldwide on an unrestricted basis and/or may not be eligible for sale to all investors. Unless cited to a third-party source, the information in this document is based on observations of CIGP. The information provided is based on numerous assumptions. Different assumptions could result in materially different results. Before acting on any information you should consider the appropriateness of the information having regard to your particular investment objectives, financial situation or needs, any relevant offer document and in particular, you should seek independent financial advice. All securities and financial product or instrument transactions involve risks, which include (among others) the risk of adverse or unanticipated market, financial or political developments and, in international transactions, currency risk. The contents of this report have not been and will not be approved by any securities or investment authority in Hong Kong or elsewhere.

CIGP acts as an agent when recommending or distributing investment products. The product issuer is not an affiliate of CIGP. CIGP is an independent intermediary, because: (i) we do not receive fees, commissions, or any other monetary benefits, provided by any party in relation to our distribution of any investment product to you; and (ii) we do not have any close links or other legal or economic relationships with product issuers, or receive any non-monetary benefits from any party, which are likely to impair our independence to favour any particular investment product, any class of investment products or any product issuer. Neither us nor our group related companies shall benefit from product origination or distribution from the issuers or providers, whether in monetary or non-monetary terms. We do not provide any discount of fees and charges.

Sources: BIS, Bloomberg, CICC, CIGP, ECB, Fed, Gov.uk, IMF, Macrotrend